What you need to know about the Colonial Pipeline hack

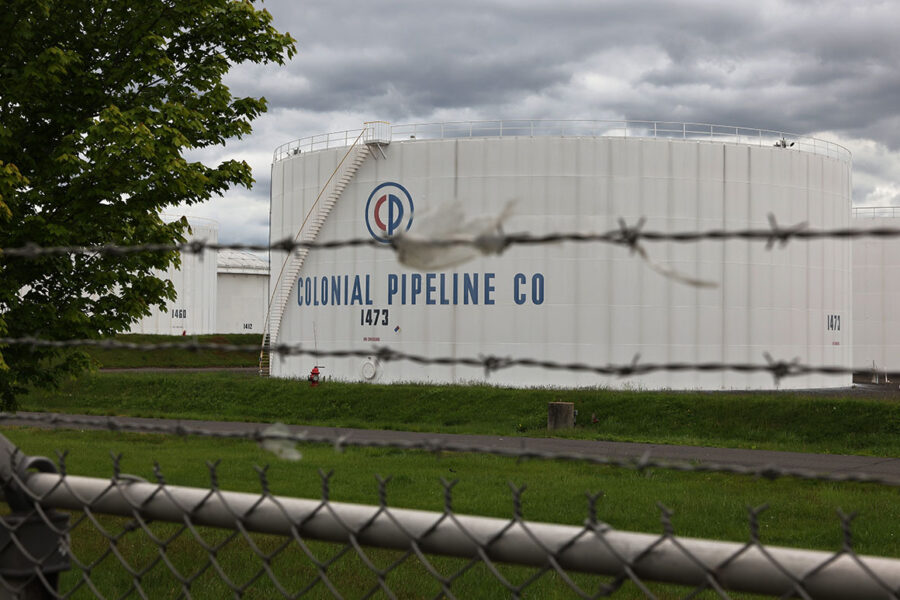

The cyberattack that forced the shutdown of the East Coast’s largest gasoline pipeline has prompted fresh questions about the vulnerability of the country’s critical infrastructure to cyberattacks.

The breach at Alpharetta, Ga.-based Colonial Pipeline is the latest in a series of cybersecurity incidents confronting President Joe Biden’s administration — as well as a high-profile reminder that many of the companies operating the nation’s most basic infrastructure, from dams to power plants, remain unprepared to deal with threats posed by malicious ones and zeroes.

Here’s a rundown of how a criminal gang managed to infiltrate Colonial’s systems and why the tool they used — ransomware — is such a persistent threat.

How did computer hackers shut down a pipeline?

On Friday, Colonial Pipeline said it learned that hackers had infected its computer networks with ransomware, malicious code used to seize control of computers and extract payments from victims. The breach affected Colonial’s business networks, which it uses for tasks such as managing payrolls and reporting data to regulators.

Colonial deactivated those systems, but it also shut off the much more sensitive technology that runs its pipeline operations — a precaution aimed at preventing the hackers from reaching it if they hadn’t already. These systems monitor the flow of gas for impurities and leaks, control power levels and perform other automated tasks to keep the pipeline running smoothly.

What exactly has been shut down?

Colonial shut down its entire primary pipeline system, which runs more than 5,500 miles from Houston, Texas, to Linden, N.J. This pipeline transports 45 percent of the gasoline, jet fuel and diesel for the East Coast of the United States, according to the company.

Does this mean the price of gasoline is going up?

The outage briefly pushed up wholesale gas prices in the financial markets in the affected region, but that rally briefly lost steam during trading on Monday. And while some gasoline retailers may try to add a few pennies a gallon to the price at the pump, no reports emerged of shortages at the suppliers that serve those retail outlets.

Market analysts said the pipeline outage would need to last until at least the middle of the week to start to affect supplies in some areas of the Southeast, and that Houston’s refineries would not begin to reduce their output unless the Colonial was out of service till next week.

Overall, the U.S. was sitting on 235 million barrels of gasoline in storage, enough to supply the country for nearly a month. Still, retail gasoline prices have been climbing steadily in recent weeks, and any jitters could accelerate the increase as the country approaches the Memorial Day weekend, which the industry sees as the start of the heavy-demand “summer driving season.”

How bad could this get?

It depends on whether the shutdown turns into a prolonged crisis for Colonial’s customers, which include busy airports and U.S. military bases. Some customers may be able to buy fuel from foreign suppliers, but they will face more financial pressure the longer Colonial’s pipeline network remains offline.

Colonial said Monday it has begun reactivating segments of the pipeline and anticipates “substantially restoring operational service by the end of the week.” However, it did not explain what it meant by “substantially” and has provided few other details about its investigation of the hack.

What is ransomware, anyway?

Ransomware is software that hackers deploy to lock up victims’ data so they can’t access or use it — in the worst case, essentially shutting down entire companies or government offices. Then, the hackers demand a ransom payment in exchange for providing a digital key that will unlock the files.

Over the past few years, ransomware has grown from an occasional nuisance to an omnipresent threat. Victims have included hospital systems, school districts and the D.C. police department, as well as many small businesses. Ransomware attacks increased by 37 percent from 2018 to 2019 and by 20 percent from 2019 to 2020, according to FBI reports. The pandemic led to a significant increase in ransomware, with the number of attacks more than doubling year-over-year, according to one report, with a particularly large surge in the healthcare sector.

The Justice Department recently launched a task force to explore new solutions to the problem. But in the meantime, the problem continues to get worse as criminals’ incentives grow.

Why aren’t pipelines and power plants better protected against ransomware?

The private companies that operate much of the United States’ critical infrastructure — its power plants, dams, natural gas pipelines and other vital facilities — have often neglected to implement government-recommended cybersecurity protocols.

While defending against foreign government hackers sometimes requires sophisticated technology that small critical infrastructure operators cannot afford, defending against ransomware does not. Using strong passwords, training employees not to click suspicious links and requiring workers to use multi-factor authentication — which involves typing in a randomly generated number after entering one’s password — can prevent all but the most advanced hacks, including ransomware. Despite years of warnings from government officials and cybersecurity experts, most companies outside of the highly regulated financial sector have not taken many of these steps.

And even the organizations that try to take cybersecurity seriously can be foiled by small gaps. A long-overlooked back-office employee or ancient computer in a closet is often the weak link that opens an organizations’ doors wide to hackers.

With so many companies leaving themselves easy targets, more cyber criminals have begun using ransomware to make money. By picking victims that they know cannot afford downtime, these criminals virtually guarantee themselves an easy profit. In addition, many ransomware operators have begun tapping into a secondary profit stream: reselling stolen data on the dark web, where sensitive personal information can fetch hefty sums.

Sitting in between victims and hackers is the burgeoning cryptocurrency ecosystem, which includes unscrupulous payment facilitators that are happy to process ransom transactions and stonewall law enforcement.

How often do victims pay the ransom?

The U.S. government discourages ransomware victims from paying their attackers to regain access to their data. While some ransomware operators honor their agreements and unlock victims’ files to cultivate trust and increase their chances of receiving future ransom payments, many of these criminals simply take the money and disappear. Paying ransoms also encourages cyber criminals to continue their attacks.

“We recognize that victims of cyberattacks often face a very difficult situation, and they have to balance the cost-benefit when they have no choice with regard to paying a ransom,” Anne Neuberger, the deputy national security adviser for cyber and emerging technology, told reporters Monday.

In the U.S., it is not illegal to pay a ransom to regain access to locked data. However, it is illegal to pay ransoms to entities on the Treasury Department’s sanctions list, and Treasury has warned companies that help victims with ransomware payments to conduct due diligence on the hackers before arranging a payment.

What is DarkSide, the group behind the attack?

The FBI has confirmed that the Colonial Pipeline hack was the work of the DarkSide ransomware gang. This group is a relatively new entrant into the ransomware ecosystem, but it is already known for its professionalism, patience and large ransom demands.

“The group has a phone number and even a help desk to facilitate negotiations with victims,” the security firm Cybereason wrote in a report last month, “and they are making a great effort at collecting information about their victims — not just technical information about their environment, but more general information about the company itself, like the organization’s size and estimated revenue.”

DarkSide is based in Russia, but so far, the U.S. has said it does not believe that the hackers acted on behalf of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s government.

“So far, there is no evidence … from our intelligence people that Russia is involved,” Biden said Monday afternoon. Still, he added, “There’s evidence that the actor’s ransomware is in Russia. They have some responsibility to deal with this.”

Like other ransomware gangs, DarkSide operates on a model known as “ransomware-as-a-service,” in which it provides code to less sophisticated hackers and helps them conduct their intrusions in exchange for a cut of their profits.

Following the intense scrutiny generated by the Colonial Pipeline hack, DarkSide appeared to be reconsidering this model. On Monday, a statement purportedly from the DarkSide hackers announced the group’s intention to closely scrutinize its partners’ planned attacks in the future to “avoid social consequences.”

“Our goal is to make money,” the statement said, “and not creating problems for society.”

What is the U.S. government doing about it?

The White House has created a working group composed of the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency; the Transportation Department’s Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration; the FBI; and the departments of Energy, Treasury, and Defense.

Those agencies are working together to prepare for various scenarios if the pipeline remains shut down, including planning for shortages and higher gas prices.

Separately, the Transportation Department exempted truckers transporting fuel in 17 states and Washington, D.C., from regulations restricting how long they can drive without taking a break. That could make it easier to get supplies to customers cut off by Colonial’s shutdown.

What don’t we know?

Here are a few questions that remain unanswered:

— Is Colonial sure that the ransomware didn’t infect any of its operational technology — the computers that actually run its pipeline infrastructure — before it shut down its systems?

— Have the hackers demanded a ransom payment, and if so, has Colonial paid it?

— How effectively is the Biden administration, with several key cybersecurity positions still vacant, supporting Colonial in its recovery and supporting other affected energy companies in their damage-control efforts?

— How long will it take for Colonial to fully restore its pipeline operations?

— What long-term damage could the hack do to Colonial?

— Are other critical infrastructure operators upping their cybersecurity defenses in the wake of the Colonial breach?

Go To Source

Author: POLITICO