The Fourth of July that Could Have Wrecked the Country

The Fourth of July began with so much noise in 1861 that a Washington newspaper reported that it “aroused old fogyism from its sleep.” Even at daybreak, there were firecrackers, small arms fire, cannonades and home-made torpedoes, in addition to the tolling of bells from every church in the city. Then, as now, many Americans measured the success of Independence Day by how much noise they could make, a tradition that had grown robust in the nation’s capital.

Still, the sound of so many explosions was disturbing in a city that was still jumpy, afraid that it might be invaded any moment by violent militias, furious that a presidential election had not gone their way.

Only a few months earlier, the Capitol had been threatened by angry mobs who tried to prevent the counting of the electoral votes that would certify Abraham Lincoln as the 16th president. As July Fourth approached, there were still many malcontents living in Washington, and Confederate troops were perilously close, roaming the Virginia countryside near what is now Dulles Airport. Many feared another assault on the Capitol by anti-Lincoln vigilantes.

The Civil War had begun at Fort Sumter three months earlier, when South Carolinians fired on the U.S. flag on behalf of a Southern Confederacy that had formed before Lincoln even arrived. The skirmishes had been small since then, but emotions were running high, as Americans argued over race, slavery, and the right of states to withdraw from the Union.

So began the strangest Independence Day in our history, a day that mixed celebration, self-reflection and a palpable tension that any spark would be enough to ignite a hot war between the armies stationed around Washington.

Yet each of these armies felt the same sentimental attachment to the rituals of July Fourth. Could it be that the holiday would bring them closer together, and reduce the chance of bloodletting? Or would over-eager celebration actually increase it, as firecrackers mingled with artillery fire? Either result was possible as the day began.

The way Washington celebrated that day went a long way to determine the republic we became. In a fraught moment, with two versions of America competing against each other, one version — of a country rooted in calm democratic protocols — prevailed over the other. Despite his lack of experience in elective office, and his meager education, Lincoln clearly won this often-overlooked skirmish. He had a better Fourth of July than Jefferson Davis. As a result, we live in a single country, instead of a Balkanized set of mini-Americas separated by military checkpoints.

As divided Americans limped toward that July 4, the cause of democracy was in deep trouble. Seven Southern states had seceded from the Union before Lincoln even arrived; four more quit after he asked for volunteers to defend what was left. To the south and west of Washington lay Virginia, the most powerful state in the Confederacy. To the north and east was Maryland, deeply divided in its loyalties. With danger on all sides, it was not clear that Washington could be defended.

But Lincoln understood two important ideas, and he brilliantly joined them together. If he called Congress into a special session, he could use democracy to save democracy, by raising spending and public support for the cause of saving the Union. By asking that session to meet on July 4, he could link his efforts to the Declaration of Independence, and to the memory of a country that began in a most idealistic way.

Lincoln had never achieved the kind of glittering career in Washington that Jefferson Davis had. His only elective office was a single term in the House, not very successful, 12 years earlier. But he had a lifelong relationship with the Declaration of Independence, which he had carefully read and re-read since encountering it, as a youth, inside a book of Indiana statutes. He seemed to grow taller while talking about it, as he did throughout his debates with Stephen Douglas. He particularly loved the second paragraph, with its promise of the fundamental rights that belong to all humans. Especially “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Together, those human rights constituted a powerful argument against human bondage.

There was also a Southern way of reading the Declaration, as a free pass for any disgruntled voters who wanted to start a new country after a disagreeable election result. Davis had floated this idea in his farewell speech to the Senate, inside the Capitol, six months earlier. He had also gone out of his way to say that Black Americans had no rights of any kind.

But Davis never spoke to the nation — either nation — on July 4, 1861. He had never shown much interest in history. And he may have found the Declaration uncomfortable for other reasons. Just when it seemed that Tennessee might join the Confederacy, the eastern part of the state issued its own “Declaration of Independence” so that it could remain in the Union. Similarly, West Virginia was leaving Virginia so that it would not have to leave the United States. Defending the right of secession could leave Davis the president of a very small country.

Lincoln, on the other hand, had a remarkably expansive understanding of the document. Its freedoms belonged to all Americans, including immigrants. In the fullness of time, he expected those freedoms to grow stronger, and reach other peoples, living in what he called “the vast future.” Us, in other words.

Lincoln also understood the power of the day itself, and on July Fourth, the members of Congress came back into the Capitol for the special session. It was a muggy day; a New York diarist who was in Washington complained of “crowd, heat, bad quarters, bad fare, bad smells, mosquitoes and a plague of flies.” But by coming back to the Capitol, in a non-violent way, Americans were reclaiming their democracy.

To seize the high ground, Lincoln worked for weeks on a carefully written message that restated the country’s highest truths, the way a Fourth of July oration should. He argued that the war was “essentially a people’s contest,” and reminded Americans that democracy required a fundamental trust in others to work. If “discontented individuals” attacked the government every time they lost an election, with false “sophisms,” and other ways of “drugging the public mind,” it would put an end to democracy everywhere. When ballots have “fairly and constitutionally decided,” there can be no appeal “back to bullets.”

As the members of Congress listened to a clerk read it, they often broke into applause, stunned that their new president had found a language so compelling.

Many others spoke and wrote about America’s meaning that day. Some Southern papers tried to argue that they were the true heirs of the Revolution; but it was hard to argue freedom’s cause in the same newspapers that advertised for a thousand slaves, as this New Orleans paper did, on July 4, or reported on a recent double-lynching, as this Memphis newspaper did, also on July 4.

After Congress received Lincoln’s message, it held a series of internal elections, for a new speaker, doorkeeper, sergeant-at-arms and chaplain, humble but important positions that help to move the people’s business forward. There were speeches, and votes, and disagreements, but all of the disagreements were resolved by the end of a long day. It would have been difficult to arrange a more fitting tribute to the idea of America.

The building was also looking better than it had for some time, with new flooring, and revarnished desks, and frescoes cleaned after having been defaced by angry vandals. A newspaper wrote, “everything is looking substantial and comfortable once more.”

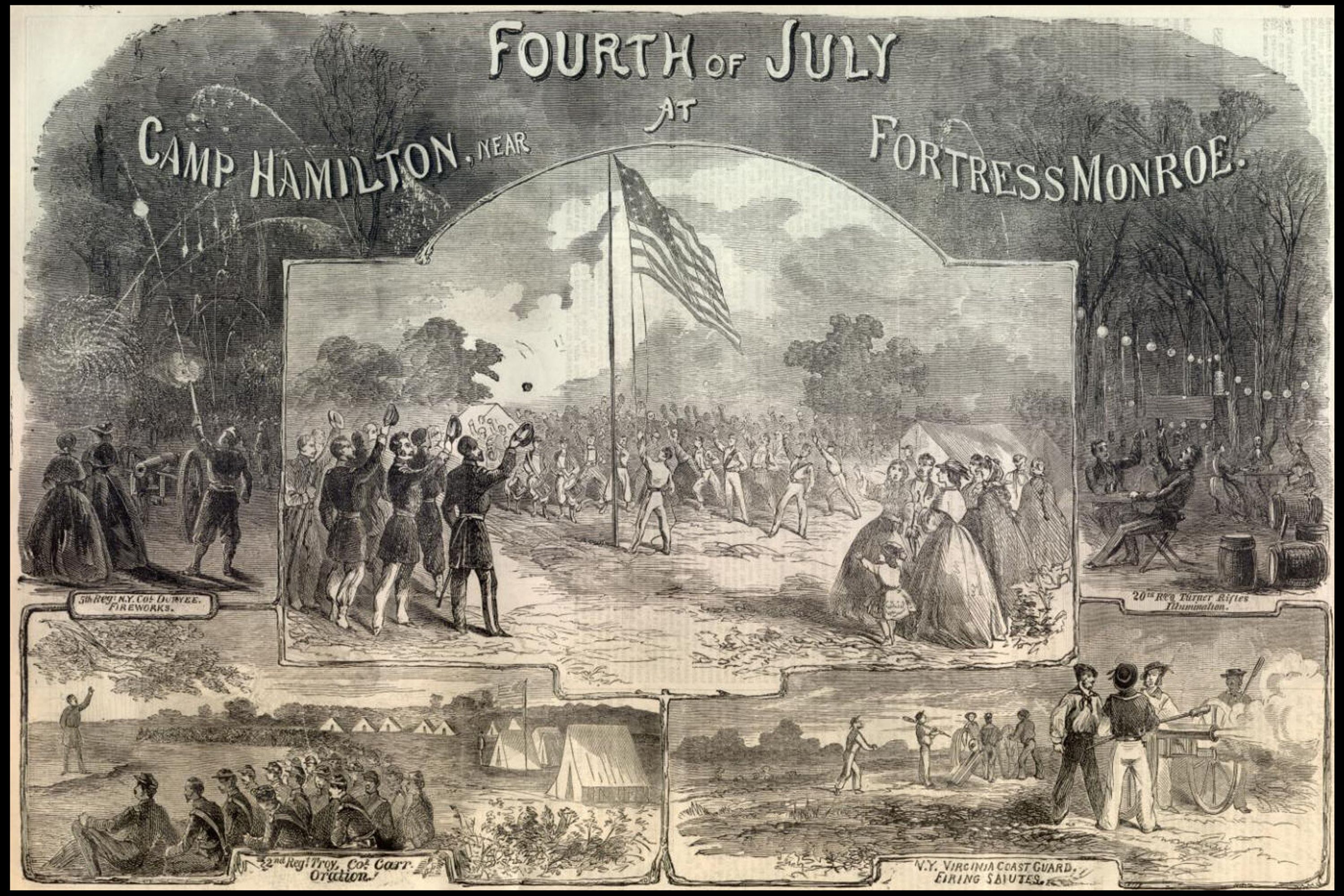

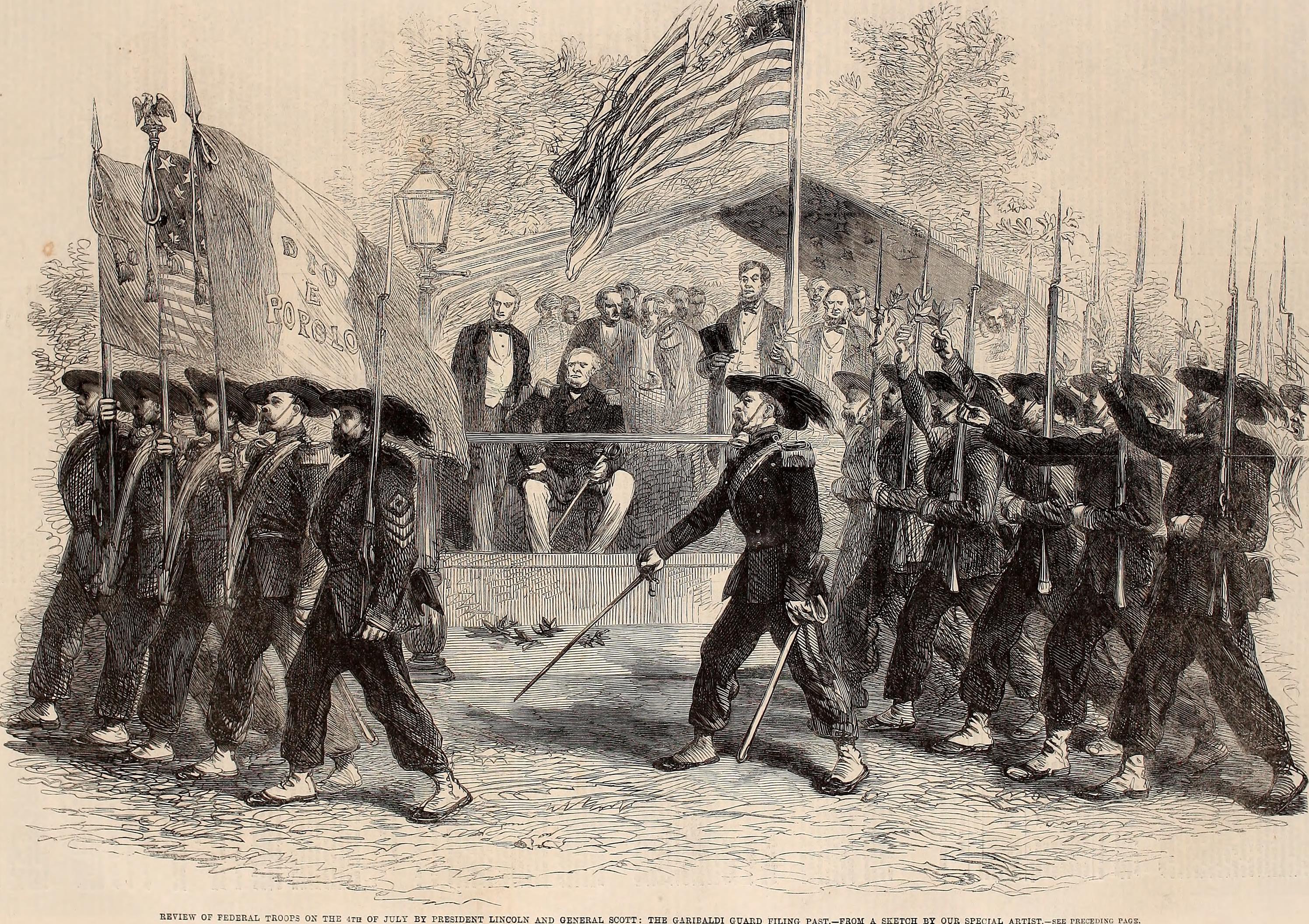

In the afternoon, Lincoln walked out of the White House and climbed the steps to a reviewing stand on Pennsylvania Avenue. There he stood as thousands of New York soldiers marched past, carrying their colors, and he hoisted a flag himself, to the top of a tall flagpole. Flags were everywhere in Washington — a paper reported, “never have we beheld half the number of flags and other patriotic emblems in our city.” The papers reported that the Declaration was read over and over again, throughout the soldier camps.

One regiment, the Garibaldi Guards, was filled with immigrants; later in the day Lincoln would visit with a regiment commanded by a Jewish colonel from Germany. When the soldiers demanded a speech, he got a laugh by saying that dignity of his position required that he say nothing at all, for fear of misspeaking.

But he had already spoken volumes through his message to Congress, and his unwavering belief in the Declaration. The real fighting had not started yet, but by winning the day, Lincoln began to win the war. Even with all of our divisions, we celebrate a single country today, thanks to a very important Fourth of July, 160 years ago.

Go To Source

Author: POLITICO