‘The Temperature in Saigon Is 105 and Rising’

As a Marine Corps veteran of Vietnam (1965-1966), a reporter who was among the last to be evacuated from Saigon by helicopter (1975) and a correspondent who covered the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan from the Afghan side (1980), I can say with authority that I agree wholeheartedly with Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s statement, “This is not Saigon.”

It’s worse.

Compared to what’s happening now in Kabul, the chaotic U.S. exodus from Saigon seems in retrospect to have been as orderly as the exit of an audience from an opera.

But there are similarities that can’t be ignored. The news and images from Kabul — the thud of helicopters, the roar of transport planes landing and taking off, along with footage of civilians mobbing the planes, desperate to get on — summon my memories of April 29, 1975, when, trapped in a city under siege, my colleague Ron Yates summed up the uniquely American feeling of empire at sundown.

“Know how I feel? The way you do at a football game when it’s the last two minutes of the fourth quarter and the score’s fifty-six to zip and your side’s the one with the zip,” said Yates, who was the Far East correspondent for the Chicago Tribune at the time.

Yates and I were huddled with around two dozen other foreigners, mostly war correspondents, in the first-floor corridor of the Continental Palace hotel in Saigon as the North Vietnamese Army rolled south. The building shimmied and shook as NVA artillery pummeled Saigon.

It was ten-thirty in the morning, and the shells had been falling for six hours. Enemy tanks had penetrated the city’s outer defenses. The day before, we had been given our instructions and assignments to evac teams, each of which was issued a Citizens Band radio to monitor coded traffic over the airwaves.

The code words we waited to hear were: “The temperature in Saigon is one hundred and five and rising,” which were to be followed by a few bars from Bing Crosby’s “White Christmas.”

The Parable of the Tamarind Tree

We did not hear it, only incomprehensible chatter on our team warden’s CB, and we wondered, “Is it still humming, is the Great American Delusion machine that for ten bloody years has predicted the shining of the light at the end of the tunnel, still churning out fantasies and slickly-packaged nonsense?” The most recent fairy tale was that South Vietnam was capable of standing on its own, capable of repelling the North’s onslaught, despite incontrovertible evidence that it was no such thing.

That collective delusion may sound familiar to veterans of the Afghan conflict.

Central to the fairy tale was the legend of the Tamarind tree, which rose in the courtyard of the U.S. Embassy in Saigon. For roughly the last month, embassy staffers had pleaded with Ambassador Graham Martin to cut down the Tamarind so helicopters could land there safely and evacuate U.S. officials and the Vietnamese who worked for them. Graham refused — felling the tree would send the wrong message to our allies, he claimed. Only twenty-four hours before, even as evacuation teams were being assigned, he had cabled Washington with good news: The situation was well in hand, cancel all evacuation plans, Saigon would not fall. Afterwards, a band of young embassy officials had bypassed Graham and given Washington the facts. The White House had cabled its reply in fifteen minutes — the evac was back on.

But huddled in our hotel within walking distance from the embassy, we were all asking ourselves, “Is it really? Does the Tamarind still stand?”

Then our warden yelled, “Choppers on the way!” and told everyone to keep quiet. He cranked the CB volume to max, and we heard:

“Diamond Control, this is Whiskey Six. Temperature in Saigon is one zero five degrees and rising. Over.”

The warden jumped to his feet, shouted: “That’s it! One hundred percent evacuation! We’re outta here!”

“Hey, they’re supposed to play ‘White Christmas,’” someone said. “They didn’t play ‘White Christmas.’”

“Fuck Bing Crosby!” hollered the warden. “It’s bye-bye everybody!”

Fleeing Saigon

Our team was bused to the military side of Tan Son Nhut, Saigon’s airport. The bus passed the U.S. Embassy, a huge fortress surrounded by a 14-foot wall topped with razor wire. The scene there resembled a soccer riot: thousands of Vietnamese trampling each other, trying to smash through the iron gates or to scale the wall. Atop it, U.S. Marine guards smashed hands and heads with rifle butts — a picture that engraved itself on my mind, that filled me with bitterness and sorrow — American Marines clubbing the people they had been sent to save ten years ago.

And as we drove toward the airport, passing sullen, frightened Vietnamese soldiers, I also felt ashamed of myself and my country. I felt like a deserter.

With NVA one-thirties pounding the airstrip, we were herded into the Defense Attaché compound. There, a semblance of order, welcome after the mess of the past few hours, had been established. Hundreds of Vietnamese, mostly military officers and their families, were crammed in with us. Marines and embassy personnel divided us into helicopter teams, issued manifest cards, told us where to assemble. We moved toward the doors. A Marine swung them open and commanded, “Go!” I sprinted for a Chinook helicopter idling in the landing zone, a tennis court, of all things. Vietnamese sprinted with me, though some were hobbled by their suitcases, filled with gold bars.

So many men, women and children piled into the Chinook that it looked like a New York subway car at rush hour. I wondered if it could lift off. It did, soared over Saigon and rice paddies and villages, and crossed the coastline. I noted the time: 4:17 pm. All I could see below were the South China Sea and ships, the warships of the 7th Fleet, civilian ships pressed into military service. They were packed with refugees.

The Chinook touched down on a carrier’s flight deck. The hatch opened, Yates and I clambered out behind a woman leaning sideways from the weight of the smuggled gold in her flight bag. A sailor slapped me on the back and said, “Welcome to the USS Denver, welcome home, buddy.”

And that’s the way it was on the last full day of America’s first lost war.

Delusion From the Delta to the Kush

How have the last days of the country’s second lost war been worse?

Well, I’ll admit it’s my impression, from watching and reading the news, that they are. In Saigon in 1975, U.S. aircraft ferried more than 7,000 Vietnamese, Americans and other foreign nationals to safety in 19 hours. Tens of thousands more were later rescued at sea. As of this writing, two days after the Taliban seized Kabul and the country, Afghans flown to safety number in the hundreds. But the main difference is that the evacuation from Saigon, though cobbled together on the fly, at least had some organization and planning. The one from Kabul appears not to have been planned at all; if it was, the execution has been dismal in the extreme.

One similarity between the two conflicts stands above others: The Great American Delusion machine operated as effectively in the Hindu Kush as it did in the Mekong Delta, producing rosy predictions of victory that were contradicted by the gloomy facts on the ground. No one in Washington imagined that 75,000 insurgents would defeat 300,000 Afghan soldiers, supported by heavy artillery and gunships, in a few weeks without expending much ammunition. The NVA had to fight their way into Saigon, the Taliban basically walked into Kabul.

The blunders, committed by three successive U.S. administrations, sprang from a number of misconceptions. The U.S. assumed Afghanistan is a country with a coherent national identity rather than what it is — a loose federation of ethnic enclaves (Pashtuns, Uzbeks, Tajiks, Hazaras) run by warlords with no abiding allegiance to a central government. And the U.S. assumed the Afghan government, despite rampant corruption and double-dealing, would eventually establish a functioning democracy, or at least a simulacrum of one.

To most Americans, Afghanistan is mysterious, utterly foreign, unknown and unknowable. Vietnam was like that. When I served there as a rifle platoon commander, we often called the United States “The World,” as if we were fighting on some alien planet. In a way, we were. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal a few days ago, Chuck Hagel, President Barack Obama’s defense secretary and a decorated veteran of the Vietnam War, stated that the disconnect between Americans and Afghans was a repeat of the one that undermined the effort in Vietnam.

“This is the lesson we learned in Vietnam, and we have to learn it in Afghanistan, and in Iraq, too,” Hagel said. “We get into these situations, we’re never sure why we’re there. We never get to learn the country, the customs, the people.”

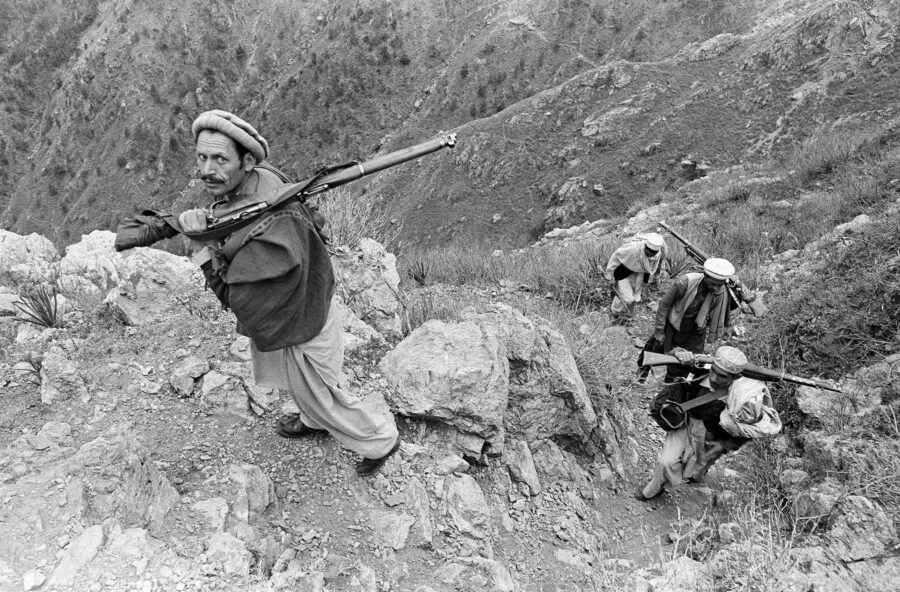

It’s a lesson we could have learned from the Russians in Afghanistan, where I spent about six weeks in 1980 with Afghan mujahideen fighting the Russians while I was on assignment for Esquire. I don’t doubt that many of those fierce warriors were the fathers and grandfathers of today’s Taliban. Some of the younger ones may be high-ranking Taliban commanders.

It was clear right away that the mujahideen were determined to expel a foreign invader, no matter how long it took, no matter how outgunned they were. Once, my photographer, an Englishman named Steve Bent, and I were hiding in a cave with a band of insurgents while two Russian MI-24 gunships prowled low and slow over the river in front of us. At the mouth of the cave, a mujahid aimed his rifle at the choppers, armed with mini-guns, rocket pods, bomb racks and electronic sensors. I prayed he would not shoot and bring all that techno wrath down on our heads. After the aircraft flew on, I asked to look at his rifle. Stamped on the receiver were the initials V.R. — Victoria Regina — and the date of its manufacture: 1878. It was a single shot Martini-Henry, the standard infantry weapon of Rudyard Kipling’s British-Indian army.

The Russians had underestimated the toughness and the bravery of their adversary. Afghans begin to learn to prevail over difficulties early in life. About a week after our experience in the cave, Bent and I were with a detachment of 30 mujahideen escorting refugees to safety in neighboring Pakistan, another week’s march away. During the trek, I took pity on a ten-year-old boy whose bare feet had been shredded. We had to cross a log bridge spanning a mountain torrent. Certain the boy would be unable to keep his balance on the single log, I carried him over. When I deposited him on the other side, his father yanked him from my arms, slapped him, then punched me in the chest. Needless to say, his reaction shocked me. The insurgents’ leader explained that the boy had to learn to survive on his own. Because of my kindness, he would expect a stranger to come to his aid when the going got tough.

The fluid and shifting alliances that characterize Afghanistan’s wars is hard for outsiders to understand, a lesson we learned a couple of days later, when the refugees, strung out in a long column that resembled a gigantic centipede, were waylaid by bandits. We saw only three of them, led by a bushy-bearded thug armed with a Russian machine gun. They were levying a toll for crossing into their territory. Although “our” mujahideen outnumbered the gang ten to one, they docilely submitted, because many more of the gang’s comrades were hidden in the surrounding hills. The bandits collected money and jewelry from the refugees. Our commander moved Bent and me to an embankment out of sight. He informed us that the bandits belonged to a rival guerrilla faction and that if they saw two foreigners, they would kidnap us and hold us for ransom. My protest, “But you guys are supposed to be on the same side,” was irrelevant.

One night, Bent and I came to a wide, raging river, the Konhara, in the middle of the night. Several hundred refugees had to be ferried across and guided into Pakistan before daylight, when Russian gunships would be patrolling the skies. The ferries were rafts floated on inner tubes and inflated goatskins, propelled by oarsmen. Loaded with people and their belongings, the rickety vessels careened downstream, the oarsmen struggling to maneuver cross current to the far side. The civilians on the near side raised their arms to heaven and shouted with one voice, “Allahu akhbar!” A man swung a kerosene lantern to signal the next craft to make the attempt. It did. The operation went on hour after hour until dawn, the crowds waiting to cross chorusing “Allahu akhbar!” each time a raft made it safely ashore. The stern faith of those people was moving, the sound of their prayers rising above the river’s roar not without grandeur. I was convinced that the Russians could do everything to the Afghans except beat them.

A dozen years after the Soviets withdrew, and for twenty years more, America tried and failed as well, re-consecrating in blood and treasure what Tsarist Russia, the British Empire and even Alexander the Great learned the hard way about “the graveyard of empires.” I think back to when I was a young lieutenant in Vietnam, listening to a friend recite his favorite Rudyard Kipling poem. The last stanza could apply to Afghanistan as much as to Vietnam:

And the end of the fight is a tombstone white with the name of the late deceased,

And the epitaph drear, ‘A fool lies here who tried to hustle the East.’

Go To Source

Author: POLITICO