The Supreme Court Case That Created the ‘Dreamer’ Narrative

Consider the backdrop against which Democrats in Congress are debating how to help the 11 million undocumented immigrants in this country: Border Patrol agents on horseback rounding up Haitian asylum seekers; toddlers huddled on the frigid floors of detention facilities under Mylar blankets; President Barack Obama’s record deportation numbers; the post-9/11 transformation of border flows into matters of national security; multiple failed attempts at bipartisan, comprehensive reform. In this tumult, one approach — one even endorsed by the Supreme Court — might seem deceptively obvious to any legislator tasked with fixing it all: First, protect the children.

But the children have come of age, and many of them want otherwise.

To anyone who has followed the serpentine turns of immigration policy in the past 20 years, it’s clear that one discrete group of undocumented immigrants has obtained a special degree of sympathy: young, high-achieving students who arrived here as minors with their families. Whether in news segments or State of the Union addresses, these immigrants became the sometimes-reluctant faces of the DREAM Act, the landmark legislation — never enacted — that would provide legal relief to individuals who came to the United States as children and met other requirements. Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program similarly focused on childhood arrivals, helping some 700,000 immigrants get through college and build their careers. Amid all these twists, the term “Dreamer” became omnipresent, helping proponents of these measures garner bipartisan support for what they described as sensible, narrow protections.

In fact, there’s another, deeper reason this narrative has stuck. Its unexpected origins can be traced not to congressional debates, but to the colonnaded marble temple behind the Capitol. In the 1982 case Plyler v. Doe, the Supreme Court held that all immigrant children, regardless of their legal status, were entitled to access public education, just like their peers born in the United States. Otherwise, the court said, these uneducated children would be prevented from contributing “in even the smallest way to the progress of our Nation.” Thanks to that decision, undocumented children who were in the country at the time, as well as future generations, found ways to excel in American schools, even if they faced a slew of obstacles once they turned 18 and began planning for college.

But there’s another, lesser-known side to the case’s legacy: Even as it protected minors, it drew a bright-line distinction between undocumented children and their parents — a demarcation that endures today. Beginning in the mid-aughts, members of Congress, activists, journalists and many citizens built on that legacy as they incorporated the term “Dreamer” into common parlance, as a way of humanizing a population that had long been called “illegal.” A specific narrative lay beneath that term: These people had been brought here as children through no fault of their own. They paid taxes and were highly educated, and, for many of them, America was the only country they knew. They were innocent.

This narrative has dominated the political lexicon of immigration reform for decades. Asked at a CNN town hall in July about a federal judge’s decision to bar the Department of Homeland Security from processing new DACA applications, President Joe Biden urged the audience to imagine a scenario familiar to so many immigrants: “You’re 9 years old. Your mom and your dad says, ‘I’m going to take you across the Rio Grande, and we’re illegally going to go into the United States.’ What are you supposed to say? ‘Not me, that’s against the law?’”

“What can a kid say?” Biden continued, raising his voice and shaking his arms. His brow furrowed: “They’ve come here with really no choice, and they’re good, good people.”

Biden was appealing not just to the large majority of Americans who support protecting undocumented youth, but also to a more fundamental conception of justice that emerged from the Plyler v. Doe opinion. Some legal experts today credit the decision with securing certain minimum rights for undocumented people and helping to immortalize the principle that the Constitution covers those outside the rigid boundaries of U.S. citizenship.

Within the undocumented community, however, more and more people today are grappling with the unintended consequences of the court’s opinion. In more than 15 interviews, current and former undocumented activists, lawyers and scholars almost uniformly rejected the term “Dreamer” and said that narrative has helped them to get ahead at the expense of their parents, who sacrificed their livelihoods to ensure their kids could have a better life in the United States. These sources variously called the Dreamer narrative a “myth,” a “fallacy” and a “mistake,” expressing reservations about the distinctions Plyler originally made between children and adults.

“When we say that kids and people like me who came when we were younger deserve special treatment, what it says is that the blame is on my parents,” says Jonathan Jayes-Green, co-founder of the UndocuBlack Network, an advocacy group focused on the Black immigrant experience, and now the vice president of programs at the Marguerite Casey Foundation. “That because they brought me to this country, through no fault of my own, they are the criminals — they are the villains of this story.”

Even Tereza Lee, whom many news outlets have held up as “The Original Dreamer” because of her role in inspiring the original DREAM Act, is unsettled by the idea that her age and achievements set her apart from other undocumented immigrants. “I’ve never personally identified myself as a Dreamer. That was a label that was pasted onto me for political purposes,” says Lee, a pianist who was selected to play with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra at age 16 and is now a professor at the Manhattan School of Music. She says she often asked journalists not to use that term to describe her. “There was a worry,” Lee eventually came to believe, “that it would separate immigrants into ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ categories.”

With Democrats in control in Washington, many advocates have been pushing the party to pass legislation that protects more than just undocumented youth. “Very early on [in the administration], we made decisions about fighting for as many people as possible, and specifically organized around immigrant youth, farmworkers, [Temporary Protected Status] holders and essential workers,” says Lorella Praeli, co-chair of the #WeAreHome immigrant rights campaign who often speaks with the White House. Months into closed-door talks in Congress, though, that kind of wide-ranging relief has remained elusive for now. Last month, the Senate parliamentarian rejected two plans to include multiple pathways to citizenship in the Democrats’ budget reconciliation bill, hinting that any proposals she might be willing to approve likely would focus on a narrower slice of the immigrant population — which, for reasons of political expediency, has often meant minors.

The focus on immigrant youth is not new, of course, and in fact is more firmly ensconced in U.S. history than many Americans might realize. Almost 40 years ago, in the understudied Plyler case, the Supreme Court came inches away from declaring that the U.S. Constitution protects all undocumented immigrants — before one justice pushed to craft a narrow rule around children. Today, what once looked like a solution has become a kind of trap. If America is going to change how it deals with immigration, among the first challenges for advocates will be unwinding the legacy of this “children-first” approach — and the powerful political currents it has swept in.

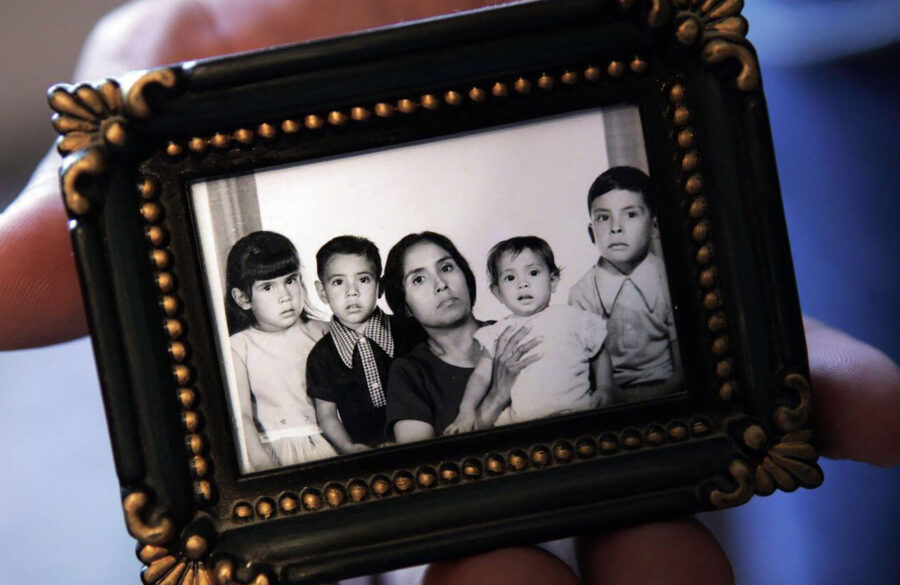

In 1977, 10-year-old Alfredo López and his siblings were sent home from school in Tyler, Texas, and told they could not come back. Two years earlier, Texas had enacted a law that denied state funds to public schools for the education of undocumented children, and authorized school districts to turn those students away. That summer, the Tyler Independent School District began requiring any student who could not produce a U.S. birth certificate to pay $1,000 — approximately $4,500 in today’s dollars — to receive an education that was free for everyone else.

A group of families, with help from the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF), challenged the law in federal court as a denial of the equal protection guaranteed by the 14th Amendment. The parents, who were allowed to proceed under the pseudonymous last name “Doe” to head off attention from immigration enforcement officials and the public, argued that Texas’ law should be struck down because their children were being deprived of any education and because they were a “politically powerless minority,” according to court documents. Tyler’s superintendent, James Plyler, argued that the children were a financial burden on the school district.

On Sept. 14, 1978, U.S. District Judge William Wayne Justice, of the Eastern District of Texas, held that the law was on the children’s side, securing a temporary victory for the plaintiffs. According to a retelling of the case in the book The Schoolhouse Gate, a bouquet of flowers soon arrived at the judge’s home, sent by three Mexican laborers who had spent $2 and change (presumably all they could afford) to express their gratitude. But plenty of other Texans directed their outrage at Justice in personal, insult-laden letters: “I would like to know your definition of ILLEGAL … Your name is Justice!” wrote one El Paso resident, doubly underlining the judge’s last name.

The case was no less contentious once it was appealed and arrived at the U.S. Supreme Court. Although some archival materials suggest a majority of the court instinctually wanted to protect the children, the justices also disagreed up until weeks before the opinion’s release about how best to crystallize the protections in law. Even if undocumented children were “persons” within the meaning of the 14th Amendment, they also had to be “within [the] jurisdiction” of the United States to be guaranteed equal protection, the school district’s lawyers argued.

The Supreme Court’s jurisprudence up until that point had established that laws that abridged an individual right based on certain protected traits or identities had to pass a higher legal standard. The segregation statutes that were challenged in Brown v. Board of Education were struck down on this basis. According to Justin Driver, a Yale Law School professor and the author of The Schoolhouse Gate, racial classifications had been accorded strict scrutiny — meaning they almost inevitably failed the court’s exacting legal test — but unauthorized immigrants had not yet been deemed part of a “suspect class,” like the children in Brown.

The swing justice at the time, Lewis Powell, a Richard Nixon appointee, was particularly torn. Powell had served on the Richmond, Virginia, school board, including during the raucous aftermath of the Brown decision and the passionate resistance against the court’s mandate. David Levi, Powell’s law clerk working on the Plyler case, said in an interview that on the morning of oral arguments, his phone rang at his desk, and he heard the justice’s Southern drawl on the other end of the line: “David, come talk to me.” The jurist was still of two minds.

“He told me that he was tending to think that these children needed relief,” says Levi, who later served as chief judge of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of California and is now a professor at Duke University School of Law. “It wasn’t like they got to vote about whether they would come across the border or not, but here they are. And it’s not in anybody’s interest that they become a permanent underclass of residents.”

Powell’s personal correspondence, housed at the Washington & Lee University School of Law and reviewed by Politico Magazine, reveals that the justice received early drafts of the majority opinion by the progressive Justice William Brennan, and that Powell ultimately persuaded Brennan to significantly narrow the opinion’s scope.

The court feasibly could have extended the Fourteenth Amendment’s protections to all undocumented immigrants instead of just children, Driver says. Indeed, the correspondence shows that the court considered enshrining such reprieve into law. When Brennan circulated a first draft of his opinion to Powell and the other justices in the majority he was trying to compose, he left open the possibility that the protections that applied to lawful residents should apply “with even greater force” to undocumented residents because they were part of a “discrete and insular minority” that triggered more intense judicial review.

But Powell, who held outsize sway as the fifth vote, saw undocumented adults as lawbreakers. “I could not agree to this,” he wrote in an early draft of his response to Brennan. In his view, “any alien beyond school age … is guilty of a crime,” and subject only to due process, not special protection under the law. Powell wrote that the draft “sweeps rather broadly,” and that he hoped Brennan would write a new opinion “focused so specifically on [children] that I can join it also.”

The justices kept going back and forth over the next six months trying to reach a majority agreement. According to legal journalist Linda Greenhouse, Justices John Paul Stevens and Harry Blackmun suggested Brennan could simply omit the reference to all undocumented people as forming part of a suspect class. Instead, Brennan redrafted his opinion so it unambiguously rejected the claim that undocumented adults were part of a protected class. On his copy of the new opinion, a satisfied Powell noted, “WJB, in this draft, has adopted the substance of my views … I believe I can join.”

When the court announced its 5–4 opinion, on June 15, 1982, the Tyler families emerged victorious, securing equal access to education for all undocumented children across the country. What’s more, the court articulated a basic principle of law that at the time was not well-settled: The Constitution preserves some rights for individuals that do not depend on their citizenship status. “Where the Constitution says ‘person,’ that means person. And that is still not a lesson learned today,” says Thomas Saenz, the current president of MALDEF. (The opinion was not without opposition: One John Roberts — the court’s future chief justice who was then a Justice Department attorney — co-wrote a memo to the U.S. attorney general disparaging the decision and arguing that the DOJ should have filed a brief siding with Texas.)

But while the opinion was a triumph for undocumented people, it also excluded most of them, drawing a stark legal line between undocumented children and adults and the protections afforded to them by law. “We reject the claim that ‘illegal aliens’ are a ‘suspect class,’” Brennan wrote in the final opinion, adopting Powell’s view. “Indeed, entry into the class is itself a crime.”

Yet, Driver points to a peculiar outcome of the Plyler case: Whereas many hard-won civil rights cases — on segregation, abortion, same-sex marriage — were decided after years-long social movements, he says, “If anything, it seems to me that you might be able to make a more plausible argument that Plyler v. Doe helped to produce a social movement.”

An unbroken line connects Plyler to the Dreamer narrative today.

In the years after the decision, Plyler earned a reputation as “the Brown v. Board of undocumented immigrants,” upholding protections in the face of anti-immigrant policies in the states. In 1994, for instance, a federal district court in California invoked Plyler when it stepped in to prevent the implementation of Proposition 187, a ballot measure that sought to deny undocumented immigrants benefits or public services, including a K–12 education. But the case remained narrowly tailored. In the same state, students who sought to expand Plyler’s protections to college education in 1985 had been thwarted.

In 2001, some in Congress decided to try to help undocumented students attend college. The Student Adjustment Act, introduced by Rep. Chris Cannon (R-Utah), would have provided relief from deportation and permanent residence to immigrants under the age of 21 who intended to attend college and met other requirements. One source who took part in early discussions of the bill, who was not authorized by their employer to speak to the press, said immigrant rights groups emphasized the principles of Plyler in discussions with lawmakers who supported the bill. Other lawmakers, such as Rep. Luis Gutiérrez (D-Ill.), introduced immigration legislation with largely similar goals.

Around the same time, Tereza Lee had been reaching out to her Democratic senator, Dick Durbin of Illinois, through a mentor who insisted she should go to college. At first, the response Durbin’s office relayed from federal agencies was disappointing, Lee recalls: “These were the government’s words — that even if I had the cure for cancer, I would still have to be deported back to my birthplace.” But Durbin, Lee says, recognized he could change the law. That exchange helped give rise to the DREAM Act, which Durbin co-introduced with Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) in 2001. The DREAM Act, whose provisions advanced the earlier, student-focused bills and eventually expanded their coverage, never passed, as Congress busied itself with formulating a response to the 9/11 attacks. But in 2006, as efforts at comprehensive immigration reform stalled, Durbin reinvigorated the push for the legislation by telling the stories of young undocumented immigrants — and explicitly appealing to the ideals of Plyler.

“Adults who enter our country illegally are responsible for their actions. They should be held accountable. But undocumented children are different,” Durbin said on the Senate floor, citing Plyler by name and quoting from the opinion in an effort to win over immigration skeptics. Undocumented children, Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) said the following year from the floor, “are technically illegal in status, but the Supreme Court has determined that these children are not responsible for the actions of their parents … recognizing that we disserve ourselves when we discriminate against them.”

As the DREAM Act was reintroduced in various forms in the years afterward — becoming a focal point of the Democrats’ agenda on immigration — the Dreamer narrative grew. Prerna Lal, a formerly undocumented immigration and tax lawyer in California, said the term “Dreamer” took off in the blossoming online blogs and chat rooms of the day, a rare venue where undocumented people felt safe enough to speak their minds, particularly as new forms of nativism emerged after 9/11 and undocumented people faced “a lot of fear” and “a lot of loneliness,” in Lal’s words. It was in one of those online forums that United We Dream co-founder Cristina Jiménez, who at the time was blogging anonymously about the DREAM Act’s progress in Congress, was first asked if she was a Dreamer, she recalls. “I have many articles in my own personal archives where they call me ‘the illegal student,’ for example,” she says. “Having an alternative word to speak about my experience that was not about being named illegal felt like a huge relief for me.”

Many organizers embraced the Dreamer label. Some came out as undocumented in public ceremonies. Others staged protests in caps and gowns to emphasize the coming-of-age milestones that were out of reach. Still others took their activism to the state level, where initiatives like Arizona’s Proposition 300 explicitly made undocumented students ineligible for in-state tuition in 2006. “A lot of Dreamers, to put it candidly, spoke English very well, had college degrees, were telegenic and appeared non-threatening — kind of this view that we are exotic, but safe,” says José Magaña-Salgado, director of policy and communications for the Presidents’ Alliance on Higher Education and Immigration, a coalition of university leaders pushing for immigration reform. By 2010, activists had garnered enough public acceptance to be present in the Senate chamber to watch as the DREAM Act died, five votes short of passage.

In response, the Obama administration — which in statements advocated for the passage of the DREAM Act as “limited, targeted legislation” meant to help “the best and brightest” — tried to step in. In 2012, exactly 30 years after the Plyler decision, President Barack Obama enacted Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, exempting young immigrants from deportation and giving them work permits if they had come to the United States before they turned 16 and met other requirements. “It makes no sense to expel talented young people … who want to staff our labs, or start new businesses, or defend our country simply because of the actions of their parents — or because of the inaction of politicians,” the president said in a speech from the Rose Garden. Although he did not cite Plyler by name, Jon Greenbaum, chief counsel and senior deputy director for the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, a civil rights group, told me, “DACA had the practical effect of extending Plyler to post-secondary education.”

The Dreamer narrative served a clear political purpose — it was a way for Democrats to slice off a portion of the immigrant community for which they could get the broadest political support, not dissimilar to Brennan’s overture to Powell in the Plyler case. For undocumented people who embraced the term, “Dreamer” helped to build solidarity around an identity and mobilize activists. It also helped to rally public support for immigrants. Alonso Reyna Rivarola, one of the founders of the University of Utah’s Dream Center, a resource hub for undocumented students that opened in 2017, told me he considered the advantages that a “Dream Center” might have over an “Undocumented Center”: “The reality is that people are going to donate to a Dream Center because it fulfills those desires and fantasies for who these innocent undocumented children are.”

Some activists use the term “Dreamer” unabashedly to this day. Astrid Silva, a community organizer and founder of Dream Big Nevada, a direct services group in Las Vegas, says that even though the elevation of Dreamers can exclude some groups, it’s also the term that prompts Spanish-speaking parents to approach her organization on behalf of their children — “because they can identify that it’s a space where they’ll be safe,” Silva says. “When we’re working at schools, they’ll drag the poor kid to me and be like, ‘Ella es Dreamer también!’” — she’s a Dreamer, too.

Yet with the benefit of hindsight, the other undocumented immigrants I spoke with nearly universally told me they believe the Dreamer narrative, set in motion by Plyler, was flawed. They point to how the focus on high-achieving minors has driven wedges between “deserving” and “undeserving” immigrants. “You put the Dreamer label on somebody, and you’re like, ‘Oh, wow, we can’t restrict the potential this person has to our society in the future,’” says Cheska Mae Perez, an organizer with Families Belong Together, a campaign of the National Domestic Workers Alliance formed in response to family separations under former President Donald Trump.

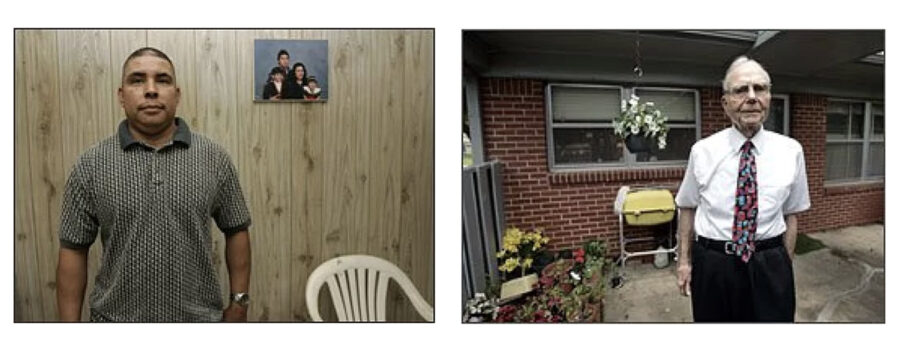

Reyna Rivarola says that, in a way, Plyler fossilized the relationship of the state to immigrants as one between a guardian and its ward: Immigrants who came to the United States as minors, even those who are now in their 30s and 40s, have had to continue to appeal to their youth and innocence to obtain government protection. “It had a huge role in painting this idea that undocumented immigrants are forever children,” he says of the Supreme Court decision.

In another way, undocumented activists came to realize that appealing to their own innocence pitted them against their parents. “There was deliberate choice-making along the way — a recognition of, ‘Wait a second, why am I getting off on telling my story in this way that doesn’t actually resonate with me?’ Because, like, I owe everything to my mother,” says Praeli, of #WeAreHome, who also was the national Latino vote director for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign.

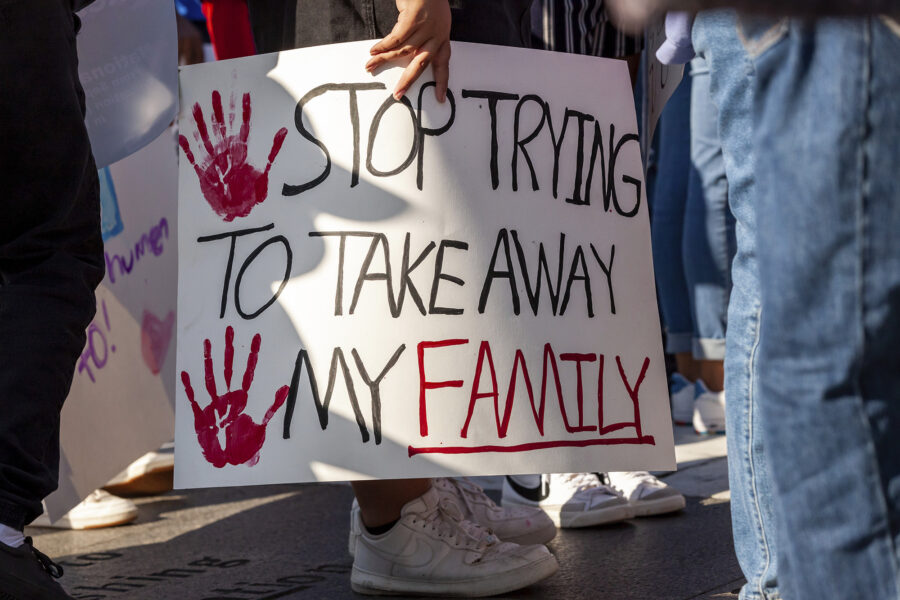

Since the Trump era, immigrant rights advocates have become even more vocal in their public rejection of the Dreamer narrative and pushed for reforms to help all undocumented people. Soon after Trump rescinded DACA in September 2017, then-House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi was swarmed by young people at a press conference in her home district protesting her negotiations with Trump over whether to enact protections for some Dreamers in exchange for a stricter deportation and border security regime. Pelosi tried to quell the activists: “For a long time, we’ve been fighting the fight for the Dreamers.” But the crowd quickly shot back: “We are not Dreamers!” Pelosi left the conference, unable to finish her remarks.

“We were pushing Democrats toward legislation that would protect immigrants without hurting immigrants,” says Adrian Reyna Chavoya, a former director of strategy with United We Dream who attended the protest. “Many times, the conversation about immigration reform is code for protection for some people in exchange for more enforcement and more criminalization of migrants.”

Several undocumented immigrants I spoke with said the movement has “grown up” in some ways, learning to build on small victories over time. After Trump rescinded DACA, Justice Action Center founder Karen Tumlin, a longtime immigration lawyer, represented DACA recipients in one of many cases fighting Trump’s rescission in the courts. Recently, while preparing for oral arguments before the Supreme Court, Tumlin says DACA beneficiaries asked her and other attorneys to avoid casting them as “deserving” of special status because they didn’t want their parents to be thrown “under the bus.” “That’s a sea change,” Tumlin says. (In 2020, the Supreme Court found that Trump had failed to follow proper legal procedure in rescinding DACA and upheld the program.)

Other organizations changed their rhetoric too, speaking in terms of “undocumented youth” instead of “Dreamers,” or abandoning the appeal to innocence inherent in saying that children came here “through no fault of their own.” Patrice Lawrence, co-director of UndocuBlack, says that moving away from the Plyler and Dreamer narrative “started to get us to a point where we could have a conversation about not who is deserving, but how we all got here.” Many immigrants from the Black diaspora, for example, came to the United States under student visas to attend college before becoming undocumented, Lawrence says, meaning they just missed the requirement that an immigrant must have entered the country before age 16 to apply for DACA.

Under the proposal Democrats intended to include in the budget reconciliation process this year, that age requirement was lifted to 18 — meaning Lawrence would have qualified. But now the party has been rethinking its plans. The Senate parliamentarian’s opinion hinted that obtaining bipartisan buy-in — which, historically, has meant focusing narrowly on young immigrants — would make it “less fraught” to include pathways to citizenship in a reconciliation bill. The Democrats’ initial plan provided pathways to citizenship for not just Dreamers, but also farm hands, pandemic essential workers and TPS holders — an estimated 7 million beneficiaries, according to the progressive Center for American Progress. Democrats have since pivoted to providing legal relief short of citizenship, hoping that a downsized measure might satisfy the parliamentarian and still help a majority of the undocumented population. At a recent Axios event, Sen. Bob Menendez (D-N.J.) said a new, preliminary proposal would provide work permits, deportation relief and the ability to travel domestically and internationally to roughly 8 million undocumented immigrants of all ages as long as they met certain requirements. The status would last five years, with the possibility of renewal for another five.

Even though Democrats have tried approaching Republicans about narrower, bipartisan efforts, Menendez suggested his party would likely have to pass immigration reform on its own. And it seems he has heard advocates’ concerns about perpetuating the Dreamer narrative. “When you talk to Dreamers, they will tell you, yes, they want to finally have their dream come true and have their status adjusted, but they don’t want to leave their parents behind,” Menendez said at the event. “So, I’m not so Solomonic to decide that I can accept a status for one group and not the other when they themselves reject that proposition.”

The Biden White House, like Obama’s before it, has continued to highlight the administration’s support for Dreamers and hew closely to existing protections. “I want to make clear to the Dreamers who are here and those who are watching from home: This is your home,” Vice President Kamala Harris remarked at the beginning of a meeting with immigrant advocates in July. Yet, many immigrants who came to the United States as minors have told me they don’t see such a stark distinction between themselves and the prospective migrants the administration has turned away, including 8,000 Haitians who were recently sent back at the border, or those who are being deported. There’s clear frustration from some activists and House Democrats, who in recent weeks have urged the vice president to overrule the parliamentarian’s advisory opinion. (The White House did not respond to requests for comment.)

The Biden administration also is working on executive action — again aimed at immigrant youth. On Sept. 28, the administration announced plans to codify DACA as an official regulation, partly in response to a Texas district judge’s conclusion in July that the Obama administration had failed to meet procedural requirements when it implemented DACA. “The proposed rule deprioritizes the removal of those individuals who came to the United States many years ago as children; have lived in the United States peacefully and productively for substantial periods; and have been or are likely to be productive contributors to American society, via education, employment, and national service,” the administration’s notice of proposed rulemaking reads.

That legal language echoes the judicial opinion written almost four decades ago in Plyler. In some ways, official Washington’s thinking continues to be molded by the notion that, when it comes to the limited set of rights that undocumented people have, exceptions are reserved for the truly exceptional.

“I wish that our people just got to be people — not extraordinary, exemplary,” says Jayes-Green, the UndocuBlack co-founder. “I wish our people every opportunity to be mediocre.”

Go To Source

Author: POLITICO