This truck driver just defeated New Jersey’s most powerful lawmaker

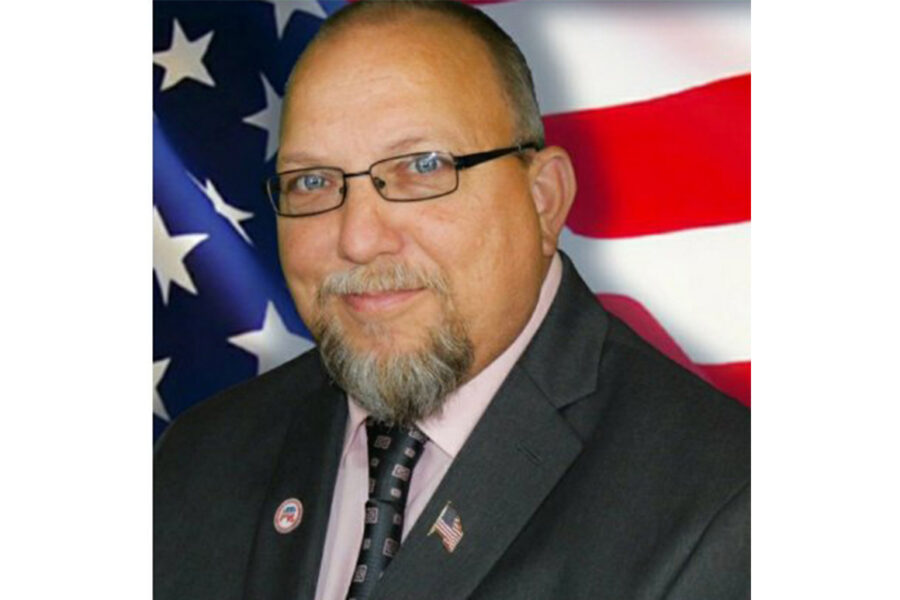

Meet Edward Durr, giant slayer.

Durr, a truck driver for the furniture store Raymour & Flanigan, was declared the victor Thursday in a race against one of the most powerful people in New Jersey: State Senate President Steve Sweeney, a top officer in the international Ironworkers union whose influence rivals that of governors.

In a week filled with surprises beyond the razor-thin New Jersey governor’s race, the election in South Jersey’s 3rd Legislative District was the biggest shocker of all — and one with massive implications for the future of New Jersey politics. Sweeney, who’s led the state’s upper legislative chamber for 12 years, was talked up in Democratic circles as a likely 2025 candidate for governor. He had amassed significant power in Trenton, shrewdly cutting deals with former Republican Gov. Chris Christie and frequently standing in the way of Gov. Phil Murphy’s agenda.

Even Durr harbored doubts about his chances and wasn’t ready to declare victory in a Wednesday interview, telling POLITICO he was “walking on eggshells” until the results became official. State Republicans quickly jumped on victory — despite deploying no resources in the race.

“I kept telling myself and telling people I was going to do it, but in the back of my mind I was like, ‘You know, how am I going to beat the Senate president?” said Durr, who ran unsuccessfully for state Assembly in 2019 and has never held elected office.

But Durr said that, as he sat in his living room with his family Tuesday night as results rolled in, it dawned on him that there was a decent chance he’d soon be a member of the state Senate — and the man who took down Sweeney.

“My daughter was sitting next to me. She laughed at me and said ‘Dad, you’ve got tears running down my face,” Durr said Wednesday morning.

Durr, a 58-year-old father of three and grandfather of six who grew up in South Jersey, estimates he spent less than $10,000 on the race. By contrast, the New Jersey Education Association, the state’s largest teachers union, spent about $5.4 million on a 2017 effort to unseat Sweeney, yet he still won by 18 points.

This was a far different election, with Republican districts and those with large blue-collar populations turning out in droves for Republicans.

It wasn’t just Sweeney. Durr’s Assembly running mates, Bethanne McCarthy Patrick and Beth Sawyer, appeared on track to defeat incumbents John Burzichelli and Adam Taliaferro (both D-Gloucester). Democrats will see their majorities shrink in both chambers of the state Legislature. And Murphy, despite claiming victory, appears to have significantly underperformed his own campaign’s expectations.

Sweeney would not concede on Thursday afternoon, dismissing the Associated Press‘ decision to call the race earlier in the morning. He remains down more than 2,000 votes but said additional ballots “continue to come in.”

“For instance there were 12,000 ballots recently found in one county,” Sweeney said in an email to POLITICO. “While I am currently trailing in the race, we want to make sure every vote is counted. Our voters deserve that, and we will wait for the final results.”

Still, trailing at all was an almost unthinkable scenario just days ago. That outcome could be indicative of a significant shift in New Jersey’s electoral landscape. Durr said Murphy’s coronavirus executive orders, vaccine and school mask mandates, unemployment benefits snafus and a general distrust of South Jersey’s Democratic machine all contributed to his strong performance.

Sweeney, Durr said, “never challenged” Murphy during the pandemic.

“You have the debacle of unemployment. The masking of the kids in school. You have Senator Sweeney trying to take away peoples’ medical freedom rights,” Durr said. “I think the perfect storm was that he stepped into a pile of you-know-what and couldn’t get out of it because he didn’t know which way to turn. I just tapped into the right focus.”

Durr, who considers himself a “constitutional conservative,” said he also sensed a backlash to the influence wielded by South Jersey Democrats, whose cohesion under power broker George Norcross had made them virtually unbeatable — until now.

“Just the constant nepotism, corruption, ‘if you take care of me, I’ll take care of you deals,’” Durr said. “You don’t have evidence, you can’t get anyone arrested or prove anything, but there’s always ‘when there’s smoke there’s fire’ kind of statements.”

Durr’s grassroots win and regular guy appeal brought him to the attention of national conservative figures, who celebrated him on social media. “Hahaha no way,” tweeted Texas Rep. Dan Crenshaw.

But New Jersey’s progressive activists were also celebrating after years of clashes with Sweeney and his patron, Norcross, whose deal-making skills kept the Senate president in power so long. Norcross frequently teamed up with Christie, most notably on paring back public worker benefits.

“He has tried to torpedo almost every important piece of legislation going back over 10 years,” said Sue Altman, executive director of the New Jersey Working Families Alliance. “The regime in South Jersey has been a complete conservation, trickle-down economics, bad-on-most-issues regime.”

Durr’s holds some deeply conservative positions. He’s advocated for cutting income, corporate and other state taxes in order for “businesses to grow,” and for reducing property taxes. He has also said that “abortion is wrong and should be stopped,” pushing for legislation that would outlaw the procedure if a fetal heartbeat is detected.

Durr said he is an ardent supporter of the Second Amendment, declaring in a recent YouTube interview that difficulties getting a concealed carry permit motivated him to seek office. New Jersey has some of the most aggressive gun control laws in the nation.

“What motivated me more than anything” to get into politics was not being able to get a concealed carry gun permit,” Durr said in the interview. “I still don’t consider myself a politician.”

Daniel Han, Carly Sitrin, Ry Rivard and Katherine Landergran contributed to this report.

Go To Source

Author: POLITICO