The Origins of Herschel Walker’s Complicated Views on Race

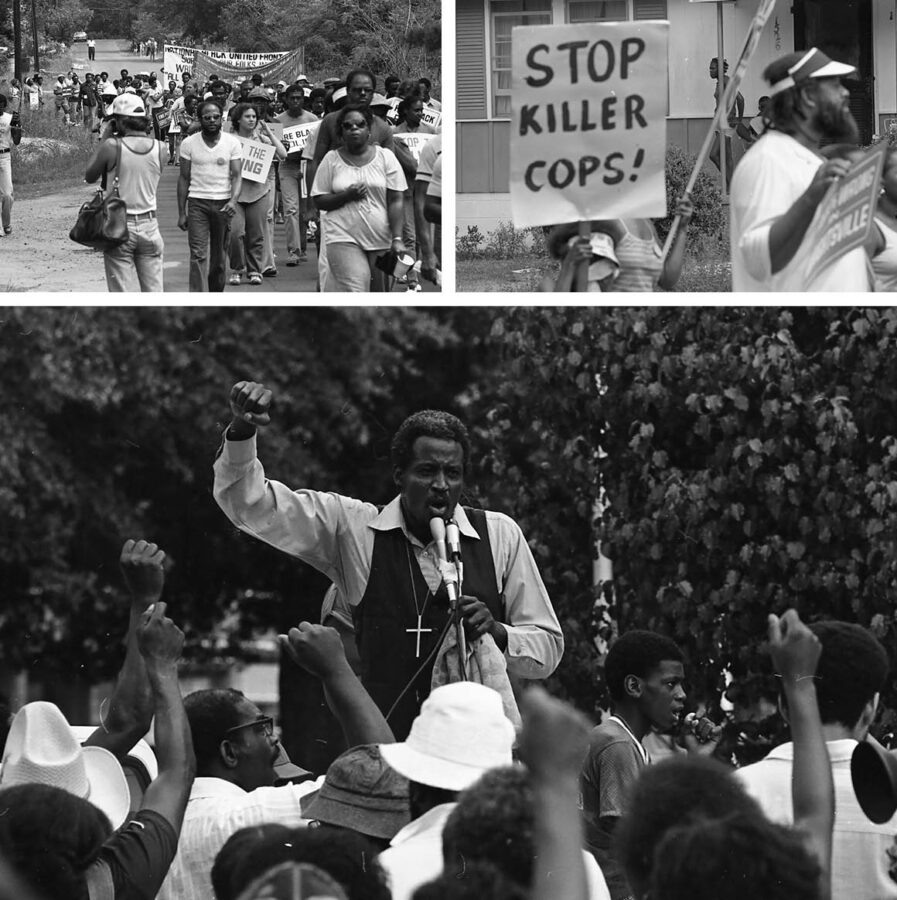

WRIGHTSVILLE, Ga. — In the spring of 1980, in this little, isolated place in rural, middle Georgia, Black people clamored for equality and white people beat them with fists and sticks and chains. Bigots called Black protesters soulless animals and cannibals, brandished Confederate battle flags and sent shotgun blasts into Black families’ homes. Pastors and activists registered voters, and sued the sheriff and other local lawmen, and they marched. “Fired up!” hundreds chanted, walking four abreast from a Black church to the courthouse in the central square. “Can’t take no more!”

For days, then weeks, then months, so many people in a town of 2,500 were swept up in the unrest, with one particularly notable exception — the area’s most prominent Black resident, almost certainly its most prominent citizen, period.

Herschel Walker.

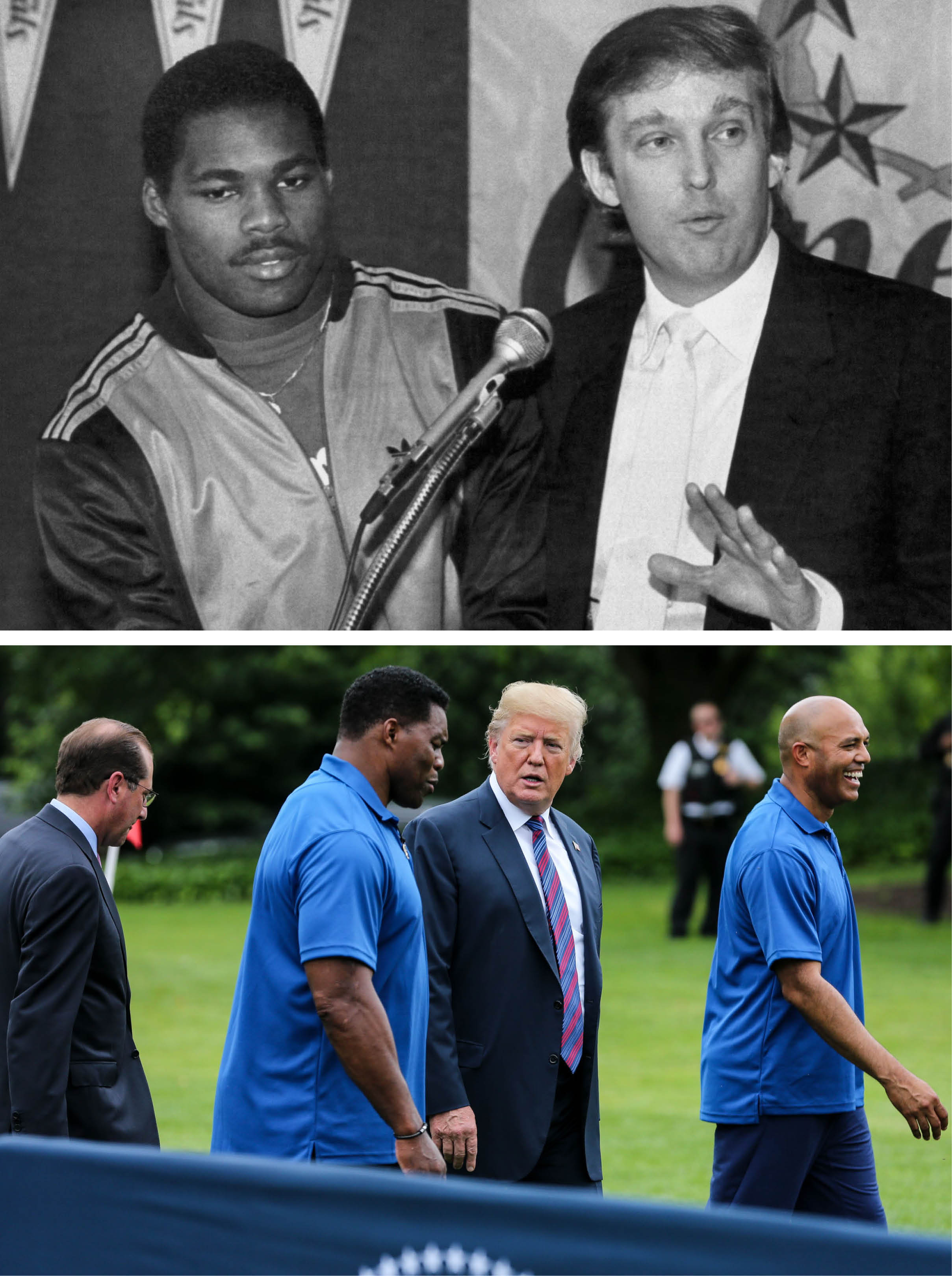

Walker, of course, is the famous former football player who is the top Republican candidate running for the United States Senate in this politically pivotal terrain. The polling and fundraising leader, Walker, 59, is endorsed by both Donald Trump and Mitch McConnell.

Back then, though, he was the most celebrated, most hotly recruited high school athlete in the whole of America — not just an all-everything running back but the president of the Johnson County High School chapter of the Beta Club of academic achievers and one of only two seniors to receive a “Citizen-Leadership Award.” In a county of not quite 8,000 that was approaching 40 percent Black but had no Black elected officials and no Black sheriff’s deputies but one Black superstar, Walker had become something like a folk hero — a favorite son who just days before had decided to great fanfare to stay in-state and attend the University of Georgia. And here he was asked, at the very outset of his life as such a public figure, by Black leaders, classmates and peers, by Jesse Jackson, by the widow of Martin Luther King Jr., to say something, to do something — to join them.

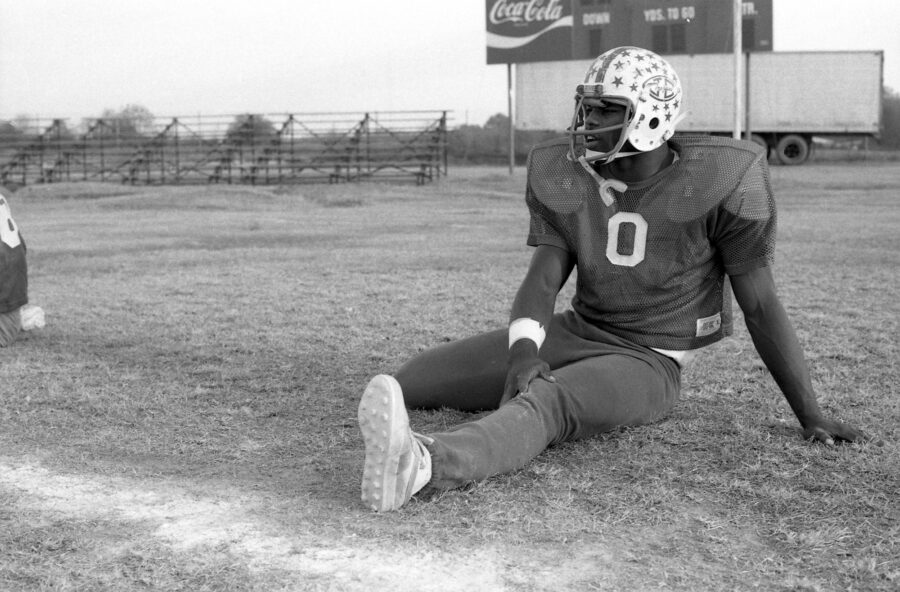

He was barely 18, but his response to those entreaties speaks clearly to who he was then and says just as much about who he is now, according to interviews with more than 40 people, including some of his closest, most important teachers, coaches, mentors and friends. An obviously promising football prospect, an uncommon combination of big and strong and fast, Walker was a budding world-class track talent, too — but he talked about wanting to be an FBI agent or perhaps a Marine. He was, thought the people who watched him and helped guide him, not exactly shy but often impenetrably withdrawn, an odd mixture of exceptionally focused and strangely disengaged. By his senior year, his athletic exploits couldn’t help but bring a brighter and brighter spotlight, but even the way he ran was telling — marked by efficiency and brutality more than artistry or flexibility. Walker ran through people and ran over people. He ran away from people. He was a reluctant celebrity.

And so that spring, as the escalating turmoil closed factories and schools and people were asked to take sides and stands, Walker could have marched. He could have played peacemaker. He could have said something or simply made a statement to one of the reporters to whom he had grown accustomed over the previous heady couple of years. He did none of those things.

“He said his Black friends were fussin’ because he wouldn’t march and the white people were calling him the N-word,” Tom Jordan, the white head coach of the track team, an assistant coach for the football team and one of Walker’s main advisers at the time, told me. “He said, ‘Coach, I don’t know what to do.’”

Jordan’s advice?

“I told him,” he said with a laugh, “to stay out of politics.”

It’s what Walker did, even as some Black students took to calling him “honky-lover” and “Uncle Tom,” while a white teammate said it “helped” that he “stayed neutral.” And it’s what he kept doing, from his standout stint in college in Athens 100 miles north to his more uneven time as a pro that included playing for a team owned by Trump to his life as an entrepreneur after that. Walker believed, he said, not in “Black and white” but in “right and wrong,” according to a biography published in 1983. “I never really liked,” he wrote in his memoir in 2009, “the idea that I was to represent my people. My parents raised me to believe that I represented humanity — people — and not black people, white people, yellow people, or any other color …”

But after a lifetime of mainly steering clear of making head-on comments on matters of racial conflict, Walker only relatively recently began to more overtly engage in the political arena — and did so on behalf of a polarizing white celebrity-politician who had earned a reputation for stoking the very racial divisions Walker says he was taught and inclined to evade. In 2015, in the initial stages of the presidential bid of his former employer, Walker made known his support for Trump. And in only the last couple years, in the wake of the murders of George Floyd in Minnesota and Ahmaud Arbery a few hours away here in Georgia, as Black Lives Matter and critical race theory and the fight for voting rights have come to define the rifts in the nation’s discordant political discourse, Walker has talked more and more about race — and in ways that echo if not outright reiterate the worldview he began to express when his out-of-the-way hometown more than 40 years back became an unlikely capital of the perpetual struggle for racial justice.

“It ain’t about African American. It ain’t about white,” Walker said in a post on his Instagram in the midst of the coast-to-coast furor in the aftermath of the police killing of Floyd. “It’s about justice.” Earlier this year he argued in congressional testimony against reparations for slavery. “Slavery,” he said, “ended over 130 years ago.” And this fall he made his first major appearance as a candidate for the Senate at a Trump rally — in a small dot on the Georgia map not that different from the one he’s from. “Don’t let the left try to fool you,” Walker told the cheering, predominantly white crowd in Perry, “with this racism thing.”

Walker’s first challenge is winning a GOP primary. Should he win, though, as expected, he will face in the general election not merely another Black man — incumbent Democrat Raphael Warnock — but a Black man who is the first Black senator from Georgia, a Black man who is an heir of sorts of Martin Luther King, the senior pastor of King’s spiritual home of Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church. Walker is a political novice — and also, by any conventional measure, an imperfect candidate, with a documented history of erratic behavior and alleged threats of violence against women that he’s partly chalked up to a rare mental health condition about which he has been eye–openingly candid. Given, though, the salience of Black voters in this state and the looming matchup with Warnock, the way Walker has engaged with race and race-related matters, and the way he has not, could be an equally or even more important facet of the coming contest, say Georgia-experienced political analysts and strategists from both parties.

“It will matter,” Democratic consultant Rich McDaniel told me. “In rural counties, places where UGA flags fly year-round, places where Grandpa might’ve been a Klansman but I’m not, he’ll get their vote if for no other reason than they get to wear it as a I’m-not-a-racist badge,” said Republican pundit Mike Hassinger. “Herschel Walker’s race will be a good test case,” added Democratic operative Kevin Harris, “where even if you are a candidate of color, can you run a race-neutral campaign in the South?”

Walker, who since announcing his candidacy in late August mostly has kept a sparse public schedule and granted friendly, limited interviews to right-wing outlets, declined to comment for this story. Talking recently, though, with one of Walker’s favorite teachers and his Beta Club adviser, I suggested that Walker at the very least would do quite well with voters in Wrightsville.

Not necessarily, Jeanette Caneega told me.

“Probably the vast majority of whites will vote for him. He has some, some Black enemies here, going back to him becoming” — she paused to think about how she wanted to put it — “a white person.”

“What do you mean by that?” I asked.

“Him not taking a stand,” she said. “You know, memories, memories — people remember things. And there’s still some resentment from even some of his classmates — Black classmates, I will say.”

The Black leaders of the protests and other Black luminaries wanted Walker to do something or say something because he was famous. He was famous because of football.

“In modern American history,” the sportswriter Jeff Pearlman once wrote, “few sports figures have possessed the mythological aura of young Herschel Walker.” He did thousands of pushups and sit-ups and wind sprints in bare feet on dirt roads while dragging truck tires lashed to his waist. In high school, unleashed, he was 6-foot-2 and 215 pounds and ran for 86 touchdowns and more than 6,000 yards and did roughly half of that in just his senior year, when he led Johnson County to a state title and was the top pick on the Parade All-America team — an all-time phenom in this nowhere burg. “Everybody here is living off what Herschel does,” a local businessperson said in a story in the Atlanta Constitution in 1979. “A hero,” said Gary Phillips, the head football coach. “Already a legend.”

The way he was raised, though, and the way he was wired, made Walker a hesitant legend, and an unlikely spokesperson, especially on the topic of race. The fifth of seven children of parents who met while picking cotton on a white man’s land, he minded his mother and father, and took after them. “He was,” the wife of the white farmer once told a reporter, “a real humble, polite colored boy.” Walker recalls in his memoir watching the Ku Klux Klan march through nearby Dublin. He tells a harrowing tale of helplessly witnessing a “fake lynching,” by jeering Klansmen with a real rickety stool and a real noose in a tree, of a “sobbing” Black child his age. “To whom could we go?” Walker wrote. “The police were white men.” Walker’s parents “did tell us stories of African-Americans who had been lynched, beaten, etc.,” as he put it, but they held no grudge, he said. “My mother and father had no ax to grind against white people.”

By the time he was in high school, Walker’s father was working at a chalk factory and his mother was working at a clothing factory owned by the same white man who owned the farm where his parents had met. Increasingly, he looked to as mentors two of the more prominent white men in town — Ralph Jackson, a farmer, and Bob Newsome, the owner of the Ford dealership. Walker as a teenager worked for Newsome, which was in step with his family’s M.O. “They endeared themselves to many old-line white families,” wrote the late Jeff Prugh, then the Atlanta-based southern correspondent for the Los Angeles Times. “If you looked at the people that were constantly invited, not only by him but his family, to functions,” Caneega told me, “they would basically be his white coaches and a few white people.”

In yearbooks from that time that I reviewed in the local library, I counted 110 students in Walker’s graduating class — 55 of them Black. Racial parity, though, did not mean placidity. “Racial tensions,” Walker wrote in his memoir nearly 30 years on, “were always present.”

When he was a junior he got one of his first lessons in what would be asked of him.

A Black classmate was horsing around in a hallway. The white principal told him to stop. “It ain’t no big thang,” the Black student said. It was indeed a “big thang,” the principal shot back, in what Black students interpreted as a racist pantomime.

“As one of the most visible African-American students at the school, and one of the student body’s leaders, I was put in a tough position. Almost all the African-American students at the school expected me to side with them in their belief that the principal, in imitating the student, had crossed a line,” Walker said in the memoir. “According to them, while the principal hadn’t used the N-word, he might as well have. The white students cited this as just another example of the overly sensitive African-American students looking for ghosts where there were none. I didn’t agree with that position, but I also didn’t want to look at this as a racial issue at all.”

It’s unclear to what extent Walker expressed to his classmates his true feelings as he tried at the time to stay out of the fray, but in the pages of the memoir he made it plain he picked a side: “In my mind, if you took out the issue of race, then the student was in the wrong. He was the one who was being disrespectful. He was running in the hallway and messing around, and if the principal, the highest authority figure at the school, asked him to knock it off and to just go about his business, then that’s what he should have done. To me, everything that happened after that was a result of the student’s lack of respect. I couldn’t get many people to see my line of reasoning, and when I didn’t come out and publicly support the allegations that the principal was bigoted, a lot of African-American students were upset with me and felt like I’d turned my back on my people.”

As a boy, Walker had stuttered and been chubby and felt teased, and so he possessed, still and in spite of his mounting renown, a disposition that tended toward isolation. Nobody knew then, including Walker himself, that he had as well the makings of Dissociative Identity Disorder, or what used to be called multiple personality disorder — but those around him the most did know Walker was taciturn and hard to read. “I always say I know him, but I always say I never knew him,” Phillips once said in a kind of odd but spot-on koan. And for all of his accomplishment and activity, Walker often retreated, seeking refuge and counsel in the homes and classrooms of his favorite coaches and teachers — the majority of them white. “By not taking sides in that dispute my junior year, I was further isolated,” he wrote. “I could never really be fully accepted by white students and the African-American students either resented me or distrusted me for what they perceived as my failure to stand united with them — regardless of whether they were right or wrong.”

It’s one of the reasons his recruitment was as protracted as it was, stretching into the spring — the 29th and last freshman of that Bulldog class to sign on. It wasn’t because Walker wanted all the attention that came with his high-profile wooing — it was the opposite. “Herschel had trouble telling anyone no,” said Jordan. “It was difficult for him to finally say where he was going,” Vince Dooley, then the Georgia head coach, told me, “because he knew that would disappoint a lot of people.”

Walker made his announcement on the evening of April 6, 1980 — Easter Sunday — picking Georgia over Clemson, Southern Cal and many other suitors. He had promised two local reporters, from the Wrightsville Headlight and the Dublin Courier Herald, they would be the first to know, and he kept his word. The reporters joined his coaches, his family and other guests at the Walkers’ house out in the country, some five miles from the courthouse in the central square.

“It will be hard to live up to the expectations of everybody,” Walker said. “I can only promise that I will do my best.”

Not 48 hours after Walker committed to play football in Athens, the Rev. E.J. Wilson, the Black pastor of the Neeler Chapel A.M.E. Church in the Black part of town, along with John Martin, a local leader for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, plus a hundred or so additional Black demonstrators, convened at the courthouse — angling for better-kept roads in Black neighborhoods, public cemeteries, parks and pools, more jobs for Black people in stores and in the town and county governments, and in law enforcement, too.

A focus of their ire was Roland Attaway — the white sheriff, by then, for nearly 20 years, widely regarded as the county’s most powerful pol. They wanted him to come out of his office to talk, and he refused, and so they shouted that he was a coward. The epithet enraged the growing group of white people that had mustered to keep watch, and they surged forward, according to the coverage of local and regional reporters on hand. Close-quarters pushing and shoving quickly became an out-and-out free-for-all.

“Attaway and his deputies were calling the protesters ‘n—–s.’ At one point, he huddled briefly with his chief deputy, then he led his deputies into the crowd,” David Lucas, a Black Democratic state representative from the area who’s still in the state senate, said at the time. “They were swinging their sticks and beating people over the head.”

Attaway called Lucas “a damned liar.” He said Black people were calling him “scum” and his deputies “trash.” Attaway dismissed the protesters as “outside agitators.”

Wrightsville was a powder keg.

“Herschel Walker notwithstanding,” Wilson said, “this is one of the most racist places in Georgia.”

A few days later, back in the square, Black demonstrators assembled, and the Klan mobilized — all of it monitored by riot-ready state troopers dispatched by the governor, the Democrat George Busbee. The Black group, led by the SCLC president, sang civil rights hymns. “White power!” the white group yelled back. J.B. Stoner, the notorious white supremacist and segregationist, reveled in his racist taunts. “We’re going to get all the civil rights laws repealed and get those jungle animals shipped back to Africa,” he said. “You can’t have law and order and n—–s too.” Stoner, who was months from being found guilty of bombing a Black church in Alabama, said he had come from his home in north Georgia to see “what the Black mob is going to try and take away from the whites.”

The menace and violence continued. In mid-April, two Klansmen sprayed shotgun shells at a Black family’s mobile home, wounding a 9-year-old girl. One especially contentious night in May, Attaway and his deputies raided churches and homes and arrested largely without warrants or charges more than three dozen people — among them Wilson, Martin and another SCLC staffer. “Somebody’s going to get killed,” a young Black person told a reporter from the Associated Press. “I’ll tell you how it’s going to end,” predicted a middle-aged man who was white. “One day, 15 of these Blacks are going to get killed, and it will be over.”

Throughout these tense, terrifying weeks and months, according to subsequent reporting in national newspapers and magazines, Black schoolmates, demonstrators, organizers and more leaned on Walker. “Demanded he join,” said the New York Times. “Pleaded,” as the Atlanta Constitution put it. “Coretta King and Jesse Jackson were calling Herschel,” Gary Smith wrote in the fall of 1981 in Inside Sports, “trying to get him to take a stand.” (A spokesperson for Jackson confirmed this to me.)

Others his age had. That spring, Jordan told me, half a dozen Black athletes on the track team quit as a form of protest. Not Herschel Walker. He didn’t do or say anything else, either — just like, it should be said, the vast majority of the 3,000 or so Black residents of Johnson County. None of all those others, though, of course, was a Georgia-bound football star. Walker reeled. He told Phillips and Jordan, his football and track coaches, he wanted to all but disappear by joining the Marines, according to the reporting of Prugh, who wrote the biography of Walker from 1983. “Tom and I told him, ‘Hey, there’s no way you’ll do that!’” Phillips said. “We said, ‘We’ll help you get through this. We’ll do something to get these people to leave you alone. Remember, we can do certain things with whites, anyway.’”

“One day he told me, ‘My friends won’t even talk to me because I won’t get involved in the protests,” Jordan told Gary Smith in 1981. “He said there were blacks threatening to kill him because he wouldn’t march and whites threatening to kill him because he was black.” When we talked last month, Jordan recalled how much that had hurt Walker. “Hurt him bad,” he said.

Hurt as he was, Walker’s stance came as a comfort to many in the white community who lauded his choice.

“Why can’t they all be like Herschel Walker?” That’s what some white people here said about Black people here, Prugh wrote. “We followed him. We looked up to him,” Buck Evinger, a white football teammate, told the biographer. “The fact that he stayed neutral helped the situation a lot.”

Not to his Black peers it didn’t. “Kids were calling him honky-lover, saying he hung around with more white people than Black,” Milt Moorman, a Black football teammate, told Smith. “If you hang around a lot of white people,” Moorman told me last month, “they start saying things.”

“He was a smart kid,” Jimmy Moore, who was a white assistant football coach, told me, “and he saw through some of the stuff that was going on. That was — I mean, I don’t know how to phrase this — manufactured maybe a little, exaggerated just a little bit. There was some strife — I mean, there’s strife everywhere — but there’s no need to go about that in that particular way.”

“He had a future, a bright future,” Curtis Dixon, who was a black assistant football coach, told me, “and he didn’t want to mess it up.”

“The family was focused on other things,” Phillips said of the Walkers. “They were not going to get embroiled in that.”

“He had a lot of pressure as a Black man from a lot of fairly powerful people in the community there, wanting him to kind of take a position,” Evinger told me. “But his position was kind of common sense: ‘I don’t really know what I think about the situation, and I’m not a spokesperson for anybody, so I’m not sure what you want me to do other than lend my name to your cause …’”

“He was all about the hate,” Caneega, who taught Walker geometry, said of E.J. Wilson, the Black pastor who was one of the leaders of the protests. “And I can’t see that he would have ever been interested in Herschel other than using him.”

She added: “I don’t think he backed away. I think he just navigated it in a very wise and thoughtful way.”

And on May 30, the most famous person ever to attend Johnson County High School graduated, one of only 12 seniors to have maintained an “A” average all four years, according to the coverage of the ceremony in the Courier Herald. Walker was one of two Black students on the 10-person Honor Guard — sort of school spirit reps. He was the only Black student among the five officers of the Beta Club. Part of the Walker lore that has hardened over the years is that he was the valedictorian, but Dixon, one of the assistant football coaches, who also taught Walker social studies, expressed to me some amusement at that, pointing out that the school didn’t name valedictorians until 1994. But Walker was, Dixon and others agreed, a very capable student — not necessarily brilliant but without a doubt diligent. And the “Citizen-Leadership Award” Walker won, the newspaper said, was given to a student who not only earned good grades but “exhibits character and leadership qualities” and participates in “social and community activities.”

The local push for racial justice, though, raged on without him. Wilson, Martin and others organized voter registration drives. They prepared a class-action lawsuit against Attaway and other local lawmen. They kept marching in and around Wrightsville.

During a march through Dublin the first week of June, Hosea Williams, the veteran civil rights activist and state senator from Atlanta, mentioned Walker. Many of the white people who knew Walker the best had seen his decision as one of pragmatic and prudent neutrality, but that’s not what some Black people saw.

White people in Wrightsville, Williams said, had made Walker an “Uncle Tom.”

“What Herschel Walker doesn’t understand is that when he stops carrying that football,” Williams said, “he has to return to the Black community.”

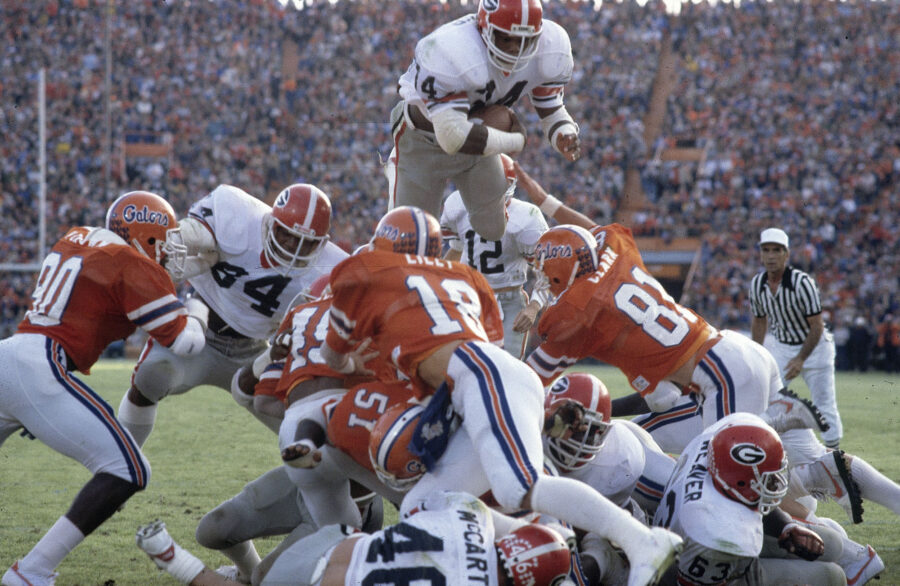

He was so good so fast in college it almost beggared belief.

Walker scored two touchdowns in his first game and three more in his second. “My God,” said Larry Munson, Georgia’s revered radio play-by-play man. “A freshman!” Over the course of the 1980 season, Walker, who had turned 18 that March, rushed for 1,600 yards and 15 touchdowns, a debut that was so stunning Walker got a few votes that fall in Georgia’s election — for president of the United States — and that was before he led the undefeated team to a win against Notre Dame in the Sugar Bowl and the national championship. “He was a legend before he ever arrived in college,” former National Football League player and sports agent Ralph Cindrich once wrote, “but he somehow became even bigger there, the Paul Bunyan of the peach trees …”

And yet Walker remained Walker.

A criminology major, he didn’t drink alcohol and ate one meal a day, slept only four or five hours a night, and in addition to being on the football and track teams took classes for tae kwon do. “People think I’m a strange guy,” he told Smith from Inside Sports. “I have friends but no best friend. You can never totally open yourself.”

He started dating Cindy DeAngelis, a white woman on the Georgia track team. Her parents didn’t like it. His parents didn’t care. Other people talked. “There has been a lot of discussion by black women,” a Black track teammate told the New York Times, “that Herschel is white-oriented.”

And as much as that attracted attention, and as much as Walker continued to try to shun the limelight, even as that became harder and harder, he still managed to typically sidestep controversy. Even when he veered toward borderline subversiveness — his openness, for instance, to the notion of leaving college early to play pro sports — he broached it in broadly palatable terms.

When a team from the Canadian Football League floated an offer after only his freshman year, Walker cast his choice to decline in practically patriotic terms. “I was born in America, and it does not seem right to leave the country to play professional football,” Walker said. “Americans should feel proud,” said Dooley, the Georgia coach. Walker later considered suing the National Football League to let him play before his graduation, contrary to convention. He invoked themes of the free market, the constitution and self-determination — but not to the point of issuing ultimatums. “I don’t think it’s right for anyone to deny me that chance,” he said in 1981. “I still feel the rule is basically unconstitutional. However, I don’t want to interfere with the system that’s designed to be the best for the majority of people involved,” he said in 1982.

“Herschel shouldn’t be underestimated,” a Black assistant vice president for academic affairs at Georgia told Sports Illustrated in 1981. “There is a kind of genius there that has enabled him to synthesize things at a much quicker rate than most adults. He’s not the kind to put an umbilical cord anywhere — even where race is concerned. He gets close to some people … at a distance. In the same way, he will never be directly offensive or affrontive.”

“He just had an ability to say the right thing,” Dooley told me recently, “so he never got into any controversy.”

“He presented himself as an extremely moderate, buttoned-down figure who was respectful of both Black and white,” Jim Cobb, a former Georgia history professor and former president of the Southern Historical Association, told me. “He was really the first Black athlete in the Deep South,” Cobb said, “to sort of achieve superstar, iconic status — and of course that process was not hindered by his demeanor.”

“His humbleness and how he carried himself and what he did for the University of Georgia — I think it changed a lot of people’s minds,” Frank Ros, a white Georgia teammate and one of his best friends, told me.

He was, in other words, a Black athlete white fans cheered and liked — in that era, more O.J. Simpson, say, than Muhammad Ali. While Walker “kept close track” of Ali, Wrightsville mentors said in 1981, he was impressed by Simpson’s “stature” and “class.”

“Herschel Walker,” Harry Edwards, the Black sociologist and longtime advocate for activism among Black athletes, once told the Atlanta Constitution, “was in good shape in Georgia as long as he was ‘the right kind of n—–.’ It’s as simple as that. That’s something Black people recognize universally in this society. As long as he restricted himself to activities and comments about what was happening on the football field, he was OK. They were demonstrating against racial injustice in his hometown, and he couldn’t come out and make a statement about it because he was eminently concerned about being above reproach as far as his credentials relative to being ‘the right kind of n—–.’”

“Down in Georgia at that time they didn’t call you Black. They called you a n—–,” Edwards told me recently. “He was simply saying, ‘I’m not going to get involved with activism, because it’s not about Black folks, it’s not about the state of Georgia — it’s about me. And as long as they think that I’m a good n—–, I got a chance.’”

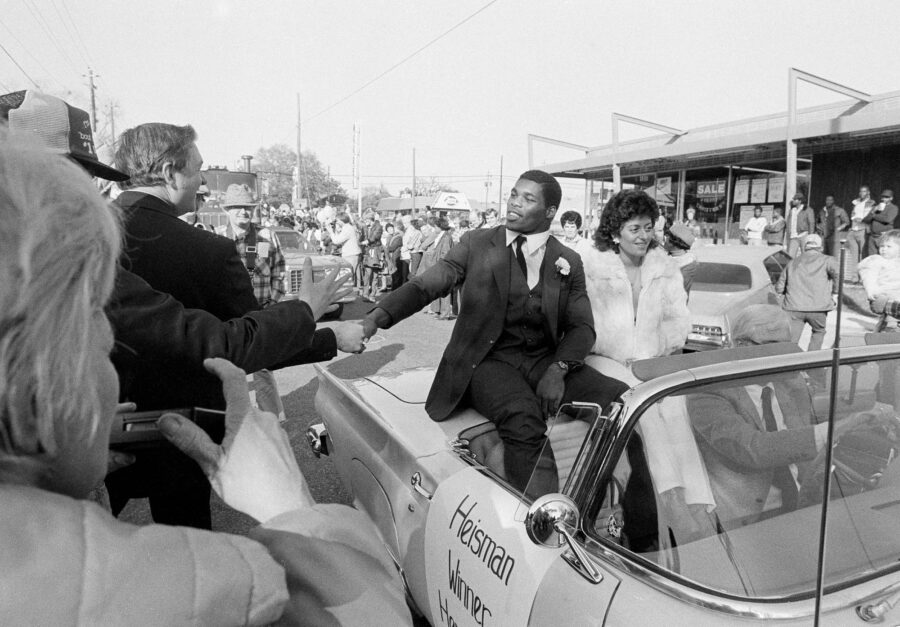

More than a chance. After finishing third in the running for the Heisman Trophy as a freshman, then second as a sophomore, he won the award as a junior — officially the nation’s best player. Wrightsville held “Herschel Walker Appreciation Day.” Walker rode through town in the back of a convertible, seated next to DeAngelis, his white girlfriend whom he would marry the following year. There in the central square, Walker was feted — by the governor, by the mayor, and by Sheriff Roland Attaway.

Two months later, in early 1983, at the federal courthouse in Dublin, an all-white jury found Attaway not guilty — saying he had not violated the civil rights of the protesters in 1980. Walker had come up in the trial. During testimony, Attaway’s attorney had invoked his name — to imply a state of racial harmony. “Was not Sheriff Attaway named Man of the Year,” he said, “at the same time Herschel Walker was named Youth of the Year in Wrightsville, Georgia?”

“Herschel,” Willis Wombles, the mayor of Wrightsville, said that March in the Chicago Tribune, “took the heat off when everybody was talking about racial trouble here.”

“Herschel,” said Attaway, “did not get involved in that trouble. He’s a fine young man. And he’s welcome here any time.”

“It’s so strange,” said Herschel Walker.

It was the middle of 1986. Walker was with a reporter from Atlanta sitting poolside at his high-rise condominium in New Jersey. He was in New Jersey because he had played his first three seasons of professional football for the New Jersey Generals, owned for the last two of those years by Donald Trump — whom Walker had added to his line of white advisers, coming to consider Trump, he would say in his memoir, “a family-oriented man” and “a mentor to me,” “and I modeled myself and my business practices after him.” He even saw, he said, a potential president. Here, though, at his condo, he was with the reporter because the reporter was working on a series of stories for the Atlanta Constitution. “Run For Respect,” it was called. “A Study of Black Football Players and the South.”

“Some people have said,” Walker said, “they thought Herschel hasn’t overstepped his boundaries in the Black-white issue — ‘he’s a good n—–.’”

He smiled. He looked at his wife.

“They always say the worst thing a Black person can do is marry a white,” Walker said to the reporter. “Did I pay attention to that?”

It had been at that point more than five years since the racial tumult in Wrightsville. Walker had not talked about it much. He said a little to Smith, and it ended up in the 1981 story in Inside Sports: “I guess it’s easier to give me a hard time than anybody else.” And he said a little more the same year to a reporter from the New York Times: “I didn’t want to get involved in something I didn’t know much about.”

But now here in New Jersey he said more.

“I am not,” he told the reporter from Atlanta, “a speaker. I am a doer. When I was in high school, people wanted me to take a stand on the racial problems. But as young as I was, how could I take a stand when I didn’t understand what they were demonstrating for? I felt I could hurt the cause a lot worse by not understanding, if I’d made a statement that was wrong.”

This, though, proved to be not so much simply a question of youth. Even as he got older, as he moved after the Trump–caused demise of the USFL to the National Football League, to the Dallas Cowboys and then to the Minnesota Vikings and then to the Philadelphia Eagles and then to the New York Giants and then back to Dallas, even as he dabbled in ballet and bobsled and mixed martial arts and founded a chicken and food business, Walker throughout and again and again made the same essential decision he had made back in the tempestuous spring of his senior year of high school. When it came to controversial social and political topics? He steered clear.

Then came Trump.

Walker backed Trump the summer he started running for president — “he is a good man,” he said — and he did his part in the 2020 reelection effort by insisting at the Republican National Convention Trump was no racist. “Growing up in Deep South, I’ve seen racism up close. I know what it is. And it isn’t Donald Trump,” Walker said. “Uncle Tom” trended on Twitter.

And in the last year and a half, as he’s waded more and more into the political fray, in particular on the topic of race, Walker often has sounded the way he sounded more than 40 years back. “We use Black power to create white guilt,” Walker said in his congressional testimony on the issue of reparations. “My approach is Biblical. How can I ask my heavenly father to forgive me if I can’t forgive my brother?” He said he had talked to his mother. “Her words,” Walker said. “‘I do not believe in reparations. Who is the money going to go to? Has anyone thought about paying the families who lost someone in the Civil War who fought for their freedom?’”

So far, it’s how he’s sounded as a Senate candidate, too. He said what he said in Perry — “don’t let the left try to fool you with this racism thing” — and he struck the same note last month at a well-attended event in Marietta. “I’m getting tired of it, because that’s how they try to separate people,” he said. “We got to get out of this racism.”

On paper as a candidate Walker is vulnerable. He’s been divorced for almost 20 years from DeAngelis, who got a protective order against him, accusing him of violent, controlling behavior. When Walker published his memoir, Breaking Free: My Life with Dissociative Identity Disorder, she told ABC News that he had pointed a pistol at her head and said, “I’m going to blow your f-ing brains out.” (He’s remarried.)

In Breaking Free, Walker says he used to sit at his kitchen table in Dallas and play “Russian roulette,” putting a bullet in a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver, “an old police-issue double-fire center-action nickel-and-steel beauty,” spinning the chamber, putting the barrel to his temple, putting it into his mouth — pulling the trigger. “I certainly came close to believing that I was nearly invincible. My alters and I had survived so much and attained such a high level of achievement the only thing left for me to do was to take on death.” Walker’s alters: He details some dozen different personalities he says he used to get through different situations — the Hero, the Consoler, the Judge, the Enforcer, the Sentry, the Watch Dog, the Daredevil, the Warrior and so on, “the essential Herschel and other satellite Herschels.”

Republican strategists and even Democrats I’ve talked to say it’s hard to use the disorder against him, given the heightened awareness of and empathy for mental health struggles — and Walker continues to be a public advocate for the importance of being open and getting help. And that’s true. Still, reading Walker’s book at times can feel like he himself provided in 2009 the first couple hundred pages of the opposition research on him in 2021 and 2022. He all but starts his story, after all, talking about the time in 2001 he considered killing a man, “how satisfying it would feel,” because this man was late with a delivery of a car that Walker had bought — Walker expressing on the page “the visceral enjoyment I’d get from seeing the small entry wound and the spray of brain tissue and blood.”

Perhaps no less important than these admissions, his past transgressions or mental health, though, is just hard electoral and demographic math. “When he stops carrying that football, he has to return to the Black community.” That’s what Hosea Williams, the civil rights activist and state rep, said back in 1980, and now, headed into 2022, Black people make up nearly a third of the registered voters in Georgia — a state in which the share of the white vote is shrinking, a state that currently has a Black man as one of its two U.S. senators, a state that came within a whisp of electing a Black woman to be governor in 2018 and will have another chance next year now that Stacey Abrams is running again.

Walker’s candidacy is prepared to highlight a fundamental and age-old conundrum in this country. What’s the most effective way to address the scourge of racial bias? Confront it out loud? Or stay mostly mum? Say it’s over and it’s time to move on in a stated stance of neutrality some find noxious or at least naïve? To whom will Walker’s positioning appeal? To which slices of which voters that could decide the winner in diversifying and tick-tight Georgia?

“It doesn’t look like the old South anymore. It’s changing. And so if you continue to run that old playbook, your math doesn’t add up. The imperative used to be to just not talk about it because the votes aren’t there — gotta be a little race-neutral,” said Kevin Harris, the Democratic operative and former executive director of the Congressional Black Caucus who has been a frequent adviser on civil rights and criminal justice. “Now it’s sort of flipped on its head, where if you aren’t race-explicit, you might have a hard time winning.”

“Herschel’s never been an outspoken person on racial matters,” a Republican former state rep told me. “And when you’ve got a guy like Raphael Warnock, who’s been on the front lines of all that for his whole public life, as pastor and now as a senator, I think that helps keep most African Americans on Warnock’s side.”

“You also have to remember how many new Black residents we have in the state of Georgia,” a former GOP member of the state’s congressional delegation told me. “And they may not even know that background,” this person said, meaning Wrightsville, 1980 and beyond. Until now.

But Mike Hassinger pointed to “probably a large, wide strain” of white Trump voters, from rich to poor. “If they have one thing in common,” said the Republican consultant and analyst, “they are f—ing sick to death of being called racists. That aggravates the snot out of them because they’re not. And they’ve never defined themselves that way. ‘I thought we were all supposed to look past each other’s skin. Black people are being racist. Why aren’t they just people?’ And they really believe that.” Those voters? “They’ll put a Herschel bumper sticker on their truck,” Hassinger said. “No question.”

Regardless, said Rich McDaniel, the Democratic strategist who led Barack Obama’s reelection efforts as that campaign’s field director here in Georgia, Walker’s stance on race, past and present, will matter. “It will matter,” McDaniel told me, “particularly if it becomes a debate about Black men and police brutality or the criminal justice system, or even voting rights. Where were you 40 years ago, or 30 years ago, on this issue, and why are you stepping up now? Why did you remain silent? Are you going to remain silent while you’re in office?”

It’s about right and wrong?

It’s not about Black and white?

“He’s going to have to explain that to voters of color if he wants to convince them that he’s going to be their advocate,” Harris told me. “That’s like ‘All Lives Matter, and that’s not gonna get it anymore,” he said. “It just makes us ask more questions. OK, well, who are your folks?”

Go To Source

Author: POLITICO